24 hours on Vancouver’s Granville Street: The good, the bad, the ugly

Fun, sketchy, vibrant, uncool, filthy: Downtown Granville’s reputation is all over the place, and has been for much of the last 134 years since the first theatre opened on Vancouver’s ‘Street of Lights.’ Now, the Strip is poised — yet again — for revitalization. Can it work?

Article content

12:01 a.m.

It’s one minute after midnight on a Friday and the Roxy is rolling. There’s a long lineup of revellers waiting out front, one of the few constants over recent decades on a street that has gone through more transformations than any other in this fast-changing city.

A dozen people are standing, sitting or lying on the sidewalk in front of the Granville Villa single-room occupancy hotel. Some are smoking opioids with glass pipes. Others are unconscious.

Advertisement 2

Article content

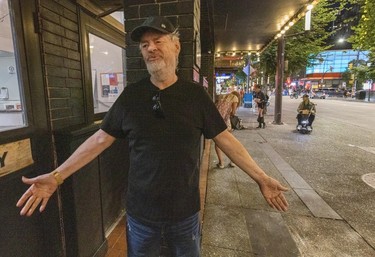

A block away is a neighbourhood fixture. The man known as “Spoons” whacks his thigh, playing his namesake instrument on the Granville sidewalk where he’s busked for almost 30 years. He says the Strip is “pretty dead” now compared to before COVID, but he’s still here performing every night. “Gotta make the rent, man.”

Article content

Local opinions about the Granville Strip — how fun or filthy or uncool or sketchy or boring or vibrant it is today, compared with some point in the past — vary wildly depending on who you ask, and when they formed their first, fondest, or worst memories of the neighbourhood.

Now, downtown Granville is poised — again — for revitalization, just as debates over many of Vancouver’s pressing issues seem to be converging on this 11-block stretch: housing, homelessness, real estate, inequality, the economy, drugs, the push to become a “grown-up” or “world class” city and how to shake off the “no-fun city” reputation.

3:32 a.m.

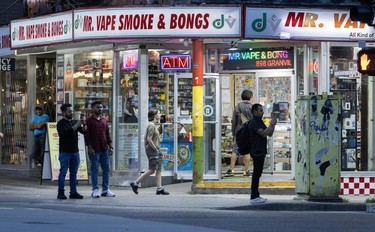

The clubs and bars have closed, but the streets, sidewalks, pizzerias, vape shops and donair joints are still packed.

4:01 a.m.

The city’s street-sweepers start their work on the Granville Entertainment District and Granville Mall. Over the next two hours, city crews will also empty litter cans and flush the alleys, getting the area ready for another day.

Article content

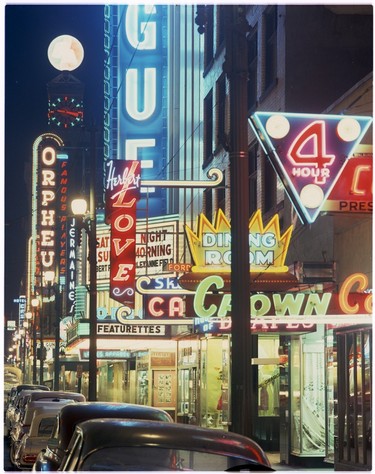

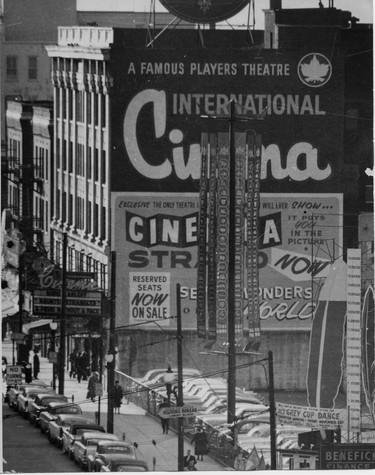

This was once Vancouver’s “Theatre Row,” starting with the Vancouver Opera House opening in 1891. Several other theatres opened, showing operas, plays, musicals, vaudeville and, starting in 1910, motion pictures.

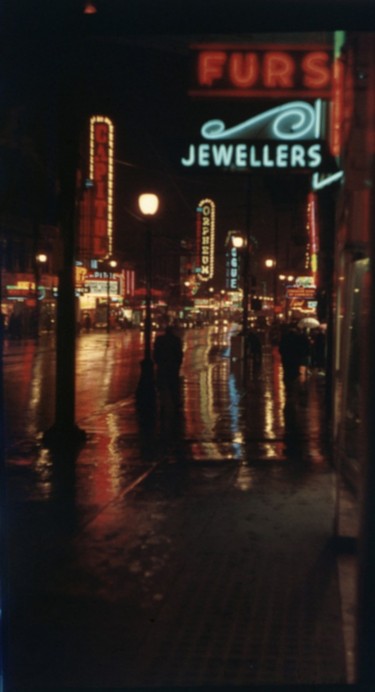

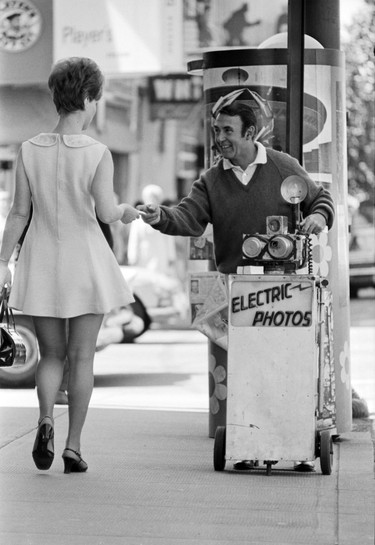

In the 20th century’s first half, Vancouverites flocked to Granville for a big night out, dressed to the nines. In an era when many people didn’t own cameras, legendary street photographer Foncie Pulice’s shots of gussied-up couples and packs of friends strolling Granville form an important part of local families’ photo albums to this day.

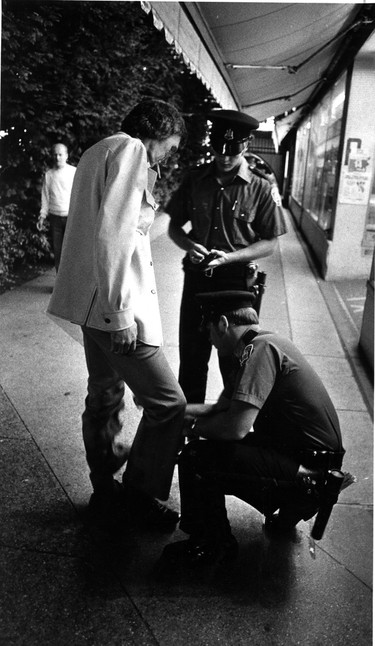

From the 1930s to the 1960s, Granville became home to more illegal gambling and drinking joints, the sex and drug trades, and the occasional “shooting scrape,” which Vancouver Sun nightlife columnist Jack Wasserman detailed in his column. The gunplay rarely showed up in police reports “because nobody ever called a cop. The beat men were usually inside the boozecans having a drink.”

By the 1970s, Wasserman declared “Granville has long been the roughest main drag of any major city in Canada.”

After decades of decay and disorder, the 1974 opening of the Granville Mall, a pedestrian and transit zone, marked the first time in nearly 40 years the street had “the appearance of going any place,” Wasserman predicted. “Frankly, it has no place to go but up.”

Article content

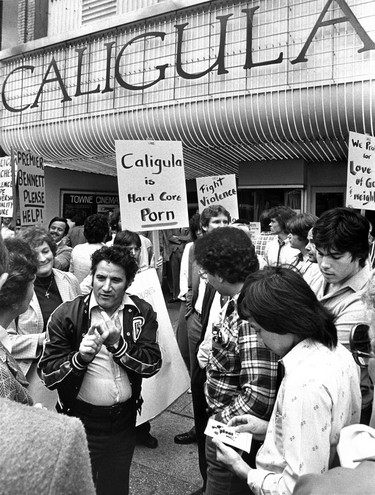

It didn’t quite turn out that way. By many accounts, the street kept deteriorating. By 1979, downtown Granville was seen as a hotbed of vice, home to so many sex shops and peep shows, porno theatres and adult bookstores, beer parlours and cocktail bars, that police were “condoning” the neighbourhood’s drug and prostitution trade, according to a consultant’s report commissioned by the Granville Street Improvement Committee.

The report’s findings were challenged by then-VPD chief Don Winterton, who said his officers had “one of the toughest sections in Canada to patrol.”

Article content

‘The Wild West’

By the 1980s, Granville “was the Wild West,” recalls Sasha Pocekovic, who started working at the Roxy Cabaret in 1988, the year it opened.

Granville didn’t have many nightclubs in those days, Pocekovic, now the Roxy’s general manager, recalled while sitting in the bar’s basement office one recent evening as staff prepared for another busy night. “We were made fun of, that we would even try to open on Granville Street.”

7:45 a.m.

After checking out of their hotels, multi-generational families of tourists speaking Spanish, German, French, and British English pull luggage along Granville towards transit or taxis. They display varying degrees of concern at sidewalk denizens lying unconscious, contorted in uncomfortable looking positions, outside of social housing buildings and vacant storefronts.

Article content

By 1995, city council considered a new move to re-energize Granville: making it a designated “entertainment district.”

That increased the number of bars in the Granville Entertainment District, or GED, through the 2000s and 2010s, as well as bad behaviour. Late-night police calls increased by more than 50 per cent between 2001 and 2006, while the number of fights, stabbings, and assaults-in-progress in the district more than doubled. Fights continued to increase over the next several years.

When COVID shut almost everything down in 2020, the B.C. government purchased the 110-room Howard Johnson Hotel at 1176 Granville and converted it into emergency social housing to get homeless people inside. Soon after, business owners started complaining about increasing crime and disorder.

Now, five years later, business owners say the area has not fully recovered since the pandemic. Some blame the former Howard Johnson — now called the Luugat — and two other nearby buildings, the St. Helen’s and Granville Villa, which have long operated as low-income housing. According to neighbourhood business owners, they’ve become increasingly problematic since COVID.

Many business owners want the social housing out of the GED, and the police and most of city council agree. In June, council approved a new plan for Granville’s next 20 years, which includes adding more hotels, rooftop patios, and nightlife — and eventually phasing out low-income housing from the central “entertainment core” between Davie and Smithe.

Article content

Some business owners — and the mayor — believe that even outside that central core, the Granville Strip is not an appropriate place for social housing. And they want the units there relocated sooner rather than later.

11:14 a.m.

On the 1100-block of Granville, a man is being arrested on an outstanding warrant outside the social housing building where he lives. It’s a calm interaction. After searching the man for weapons, the cop lets him finish his bag of chips before handcuffing him while they wait for a police van, where he’s promptly loaded into the back.

‘Cusp of an upswing’

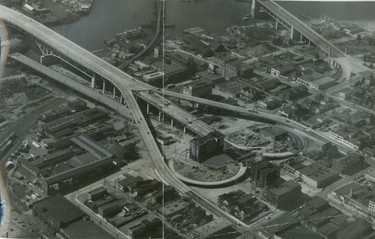

You can see early pieces of Granville’s transformation before you enter the Downtown peninsula. A protected walking and cycling path across the Granville Street Bridge’s west side opened last month after 2½ years of work. At a ribbon-cutting event, Mayor Ken Sim appeared where the bridge’s northern off-ramps once stood, declaring the new infrastructure a “game changer.”

The city has now replaced those off-ramps with a new road network that includes Neon Street, an allusion to the 1950s, when Granville was “the Street of Lights,” the glowing centre of a city with 19,000 neon signs — more than Las Vegas, according to the Museum of Vancouver.

Article content

On the former site of the ramps, the city plans to build towers between 27 and 40 storeys, with a mix of condos, market rentals, social housing, child care, and commercial space. Those projects, combined with a planned pair of 54- and 40-storey market rental towers on city-owned property around the corner, are expected to bring thousands of new full-time residents to this area, including many earning high incomes — the city-owned market rentals are aimed at households earning as much as $194,000 a year. It could bring a lot of body heat — and a different crowd — to the Strip’s southern end.

Two high-profile developments are expected to help usher in downtown Granville’s new era. On Granville and Davie’s northwest corner, where for decades Tsui Hang Village Chinese restaurant served “cold tea” to late-night sippers, a 33-storey, 464-room hotel has been proposed.

An even larger proposal has been pitched for a famous Granville property, with Bonnis Properties proposing to transform almost the entire 800-block. The project would retain and renovate the Commodore Ballroom and below-ground bowling alley, and create a viewing deck above the heritage building, which would be sandwiched between two towers with rental homes and a hotel.

Article content

This is not the last chapter for Granville, but we’re hoping it’s going to be a super-exciting one.

Neil Hrushowy, Vancouver’s director of community planning

City planners have “high hopes” that those two major projects will advance soon and “catalyze” a wave of investment and development in the area, said Neil Hrushowy, Vancouver’s director of community planning.

Granville “is on the cusp of an upswing,” Hrushowy said. “I have no illusions it’s in a tough spot right now, we all recognize that. But there are some big pieces that are changing that.”

He’s reminded of Yonge Street in Toronto, where he grew up, or San Francisco’s Market Street, where he worked before moving to Vancouver. These kinds of main drags are often derided, always evolving, and important for big cities, he said.

“These are the main streets of these cities. They will always be reinvented, that is their nature,” he said. “This is not the last chapter for Granville, but we’re hoping it’s going to be a super-exciting one, because if you look at the level of commitment and passion that we heard in the public hearing, people are desperate for Granville to work.”

“It shouldn’t be sterile. It should be a little bit messy. It should be vibrant. Should be really diverse. It shouldn’t be too controlled — those things are dangerous for great streets and great public spaces. So it is a little bit of threading the needle. But actually, I think we’re sitting in a pretty good space to do that.”

Article content

2:30 p.m.

Three police cars and two fire trucks pull up outside the Regal Hotel, another old low-income housing building on Granville, but not one of the three provincially owned hotels set to be relocated. A member of the Granville Community Policing Centre says the emergency response is for a mental health-related call, possibly a tenant barricading themselves in their room. “Nowadays, nothing out of the ordinary,” he says. “Maybe like 10, 15 years ago, a little out of the ordinary. But we try to do the best we can.”

Granville’s revitalization seems to be a big priority for Sim, who often speaks about bringing more vibrancy, investment, and “swagger” to the Strip. As a kid growing up in Vancouver, he remembers watching the original Star Wars at the Capitol 6 with his dad, buying comics at Golden Age Collectibles, and seeing Bryan Adams at the Orpheum in 1984, the night the local rocker filmed a concert video.

“It’s a street that, you can make an argument, hasn’t had the right type of attention,” Sim said. “Now we’re giving it the right type of attention. We’re saying to the entire city, the province and the country that this is super-important. We’re investing our time and effort into making the Granville Entertainment District one of the most iconic entertainment districts on the planet.”

Article content

Article content

‘We have today issues’

Sim’s office has been pushing the provincial government to move what he calls the “inadequate” social housing facilities off the Strip and put those tenants elsewhere in the city. Last month, Sim announced his office has provided the province a list of five city-owned sites in other neighbourhoods where those tenants could be moved, saying it was “never a good idea” to house people with complex mental health and substance use challenges in an entertainment district.

I’ve seen everything. The good, the bad, the ugly. And this is probably the lowest it’s been.

Bill Kerasiotis, co-owner of GoodCo

After months of pressure from owners of nightclubs and other businesses in the area, the province agreed in June to relocate the housing. Housing Minister Christine Boyle confirmed the B.C. NDP government supports Vancouver’s plan for the Strip and replacing the SROs with purpose-built supportive housing elsewhere.

“We have been working on plans to replace single-room occupancy homes,” Boyle said. “We are closely working with city staff to determine viability of the sites and an agreed path forward.”

Asked for a time frame on the relocation of those 283 units of housing, a ministry spokesperson said it’s too early to know.

That response is demoralizing for business owners like Bill Kerasiotis, who says his Granville bar Good Co. is struggling because of the government’s lack of urgency to fix its mistakes. “What does that mean? Two years? Five? Ten?”

Article content

Kerasiotis’ family has been in Vancouver’s nightlife business for decades, and he recalls city hall’s 1990s push to create a designated “entertainment district.” That plan aimed to move nightclubs to Granville and away from nearby neighbourhoods like Downtown South and Yaletown, which led to the Kerasiotises transferring the cabaret licences for Luv-A-Fair and Graceland, on Seymour and Richards streets, to converted movie theatres-turned-nightclubs on Granville, the Caprice and the Plaza, in the late ’90s and early 2000s.

Kerasiotis, like some other longtime Granville bar owners, said the years before and after the 2010 Vancouver Olympics were a particularly great time on the Strip. It started declining a bit before COVID-19, he says, and has worsened since. He believes the increase of people with complex drug and mental health problems is driving away other people, including his potential customers.

“I’ve seen everything. The good, the bad, the ugly. And this is probably the lowest it’s been,” he said.

Kerasiotis said he’s not opposed to city hall’s plan for Granville Street’s next 20 years, but he said it’s hard to think that far in the future.

“We have today issues,” he said. “We’re trying to get through those.”

Article content

6:41 p.m.

Crowds are already queuing outside the Vogue. The Commodore lineup will start soon. Portuguese-speaking 20-somethings sip cocktails on streetside patios.

These woes are not limited to bar owners. Retailers, restaurants and other businesses are changing their hours in response to neighbourhood disorder, beefing up security, or just closing up shop. Vancouver’s citywide storefront vacancy rate is 10.2 per cent, above the five-to-seven per cent level considered healthy. Downtown Granville’s storefront vacancy rate was 22 per cent last year, and jumped to 30 earlier this year.

Those numbers worry Jane Talbot, president and CEO of Downtown Van, an association representing 8,000 businesses of all kinds throughout 90 downtown blocks, including the Granville Strip.

“Downtowns across Canada and up and down the west coast are experiencing the same sorts of conditions and our 90 blocks is no different,” Talbot said. But, other parts of Vancouver’s downtown “are not really at a tipping point like Granville Street is.”

Talbot’s organization supports city hall’s plan for Granville, she said. “I can hear the voices of our members in that plan. … But they’re telling us they can’t survive on a beautiful vision.”

Article content

Talbot wants the city to take immediate, short-term actions like more security guards on the street and improved lighting, while the city waits for the longer-term changes to unfold over years and decades.

“It’s hard to visualize 10 years down the road when, in some cases, you can’t see past a month from now.”

8:34 p.m.

In a Turkish-owned pizzeria, an employee from Mexico serves a group of Irish youths while Colombian reggaeton music plays. On the sidewalk outside, a group of eight food-delivery drivers congregate, perched on their electric bikes equipped with insulated containers on the back, waiting for their next order.

Kevin Doig sits in the Luugat’s second-floor common room talking about his neighbour’s arrest earlier that day on the sidewalk outside, when he pauses mid-sentence as he notices a matchbox-sized cockroach crawling down the wall, inches from his face.

“Sorry,” he offers, before resuming his story. Six minutes later, as the roach makes its way back up the wall, Doig crushes it with a loud smack of his large fist. This time, he doesn’t miss a beat in his story.

Article content

Problems at the Luugat, where Doig has lived for three years, come from different sources, he says: from the converted hotel’s drug-addicted tenants, from non-residents who congregate outside to consume, buy and sell drugs, and from drunken hordes of partiers noisily streaming out of nearby nightclubs in the wee hours.

Article content

Still, he says, the Luugat is definitely better than the “rowdy” Downtown Eastside SROs and “no holds-barred” shelters he’s been in before. On Granville, he’s close to his doctor, transit, and affordable daily needs like coffee, groceries, and second-hand clothes.

Doig moved to Vancouver from Ontario in 2009, and remembers Granville at that time as “touristy, pricey, and a lot cleaner.”

“Back then, you didn’t see people sleeping on the sidewalk.”

Since 2020, Vancouver Fire Rescue has responded to 906 calls at the Luugat, including 375 medical incidents and 43 fires. Across the street, St. Helen’s — or “St. Hell’s” as someone wrote by hand on the front door — had 1,297 calls, including 31 fires.

Granville bar owners say the social housing is scaring away customers and killing their business, and together have started exploring the possibility of legal action against the province to seek compensation for lost business.

For the last 19 years, Alan Goodall has run a series of nightclubs in the ground-floor space below the HoJo-turned-Luugat. Since the hotel became social housing, Goodall says his club, now called Aura, has been flooded 200 times. In one month alone, major flooding triggered by fires above caved in his ceiling on three different occasions.

Article content

People in the Luugat have thrown things — rocks, liquids, garbage and, on at least one occasion, human excrement — from the windows onto club-goers waiting in line on the sidewalk, Goodall said.

Across the street, the Cabana nightclub operates below the St. Helen’s. The club’s owner, Paul Kershaw, has been operating nightclubs on Granville since he opened Stone Temple Cabaret in 1996, and says the Strip is in the worst shape he’s ever seen.

“It’s a miserable failure, the last five years,” Kershaw said. The social housing tenants are not receiving the help they clearly need, he said, and meanwhile “they’re destroying people’s businesses, and putting a black eye on the entertainment strip of Vancouver.”

But for Donna-Lynn Rosa, supportive housing is “not the problem. It’s part of the solution.”

“We understand the desire for revitalization and the very real challenges businesses face on Granville Street. But this vision cannot come at the expense of those most vulnerable,” said Rosa, CEO of Atira, the non-profit organization that currently manages both the Luugat and St. Helen’s.

“Instead of scapegoating supportive housing, we need to understand the immense challenges involved in operating some of the city’s most under-resourced and complex sites,” Rosa said.

Article content

Atira has managed St. Helen’s for more than 15 years, and the Luugat since its conversion to social housing in 2020. But that changes next month, when other local non-profits, PHS Community Services Society and Community Builders Group, will take over operations of the two buildings.

A B.C. Housing Ministry spokesperson said the transition of operations stems from a 2023 forensic audit of Atira — which found problems with financial record-keeping and violations of conflict-of-interest rules — and to let that organization “focus operations on woman fleeing violence and LGBTQIA2S+ populations.”

Article content

‘Moving in the right direction’

10:01 p.m.

Lookie-loos on the sidewalk outside the Roxy peer into the bar and comment that it looks empty. A doorman advises: “It’ll be packed in about an hour.”

Other changes are coming to the former “theatre row.”

At 855 Granville — where the Palms Hotel opened in 1913, the Paradise Theatre opened in 1964, and the Granville 7 Cinemas ran from 1987 until 2005 — Cineplex completed a nearly four-year-long renovation late last year. The result is called the Rec Room: a 45,000-square-foot entertainment facility featuring games, darts, axe-throwing, minigolf, live music and comedy, a 160-seat restaurant, and pool tables. It has an indoor capacity of 1,594 people.

Article content

Ken Mont, Cineplex’s executive director of southwest operations in B.C., won’t say how much the renovation cost, but only that it was one of the company’s largest Canadian projects in recent years.

Although business owners in Vancouver often complain about the municipal government’s onerous and Byzantine process for commercial renovations, especially for big projects incorporating old buildings, Mont says Cineplex found city hall “really good to work with.”

“I think they were very amenable to having something new on this strip, and an investment on Granville,” he said.

Mont moved to Vancouver in 2003, to manage the Capitol 6, across the street from where the Rec Room now stands, in the final years of that theatre’s run. When the Cap 6 closed in 2005, it was Granville’s last theatre — curtains for “theatre row.”

Mont and his wife had moved from Calgary. They lived a block off Granville at that time, he said, “and we liked being somewhere where the lights stayed on after dark.

“I liked the mix of people. There were people coming for the theatre, concertgoers, the club scene, the bar scene. It always seemed to be moving,” he said.

Now, the Rec Room is bringing different mixes of people to the Strip, including daytime corporate parties and kids.

Article content

“The more we can bring different people on the street, I think that’s probably better for all of us businesses here,” he said. “Different demographics throughout the day.”

10:46 p.m.

Bradley McElroy, is standing and smoking a cigarette by himself. He has lived in the Villa for the last five months, which, he says, is “five months too long.”

McElroy, 66, grew up on the same street, but in a different world.

He remembers trips from his childhood home at 33rd and Granville, and watching James Bond movies at theatres on the Strip. In the ’60s and ’70s, he recalls, downtown Granville was nice. Today, it’s “scummy.”

He doesn’t like the SRO he now calls home, he says, but it’s better than the homeless shelter where he lived before, where he had some troubles. Asked where he would go if he could live anywhere, he doesn’t hesitate: “33rd and Granville.”

Pocekovic, the Roxy manager, has worked on Granville longer than most people in his business, and strikes a more optimistic tone than many of them. The Strip is safer these days, he said, and “moving in the right direction.”

The different bar owners now work together more than in past decades, along with the police, city hall, and the province, Pocekovic said. “We’re on the same page now, we’re not adversaries anymore.”

Article content

City council’s decision last month to extend liquor service to 4 a.m. was praised by Pocekovic and others in the industry.

“I was here when you couldn’t get a drink on Sunday. The city has come a long way,” he said. “It’s a 24-hour grownup city.”

11:58 p.m.

Liam Menard, an 18-year-old from Aldergrove, is on the 1000-block of Granville with his friends. He loves the Strip. He’s here almost every day, he says. “Daytime, nighttime, daytime-till-nighttime, everything.”

Menard thinks the area’s homeless people and SRO residents get an unfair rap because of their appearance, “but they’re the nicest people,” he said. The area’s real problem, he said, is “little kids” as young as 15 who “come down here on the SkyTrain with their ski masks and their side-bags, trying to go at everybody.

“I watch out for the kids more than I watch out for these guys,” Menard said, gesturing to the people sitting on the sidewalk outside the Granville Villa inhaling drugs from glass pipes.

Granville “gets better by the year, I can’t lie,” Menard said. “From last year, to this year, I can see a big improvement, just on the amount of people down here. … I love the people around here, they know how to boogie.”

dfumano@postmedia.com

Scenes from Granville Street’s past and present

Article content

Article content