‘Believe that you belong’: Sport sets girls up for success, but gender barriers remain

When 16-year-old Hannah Connors hits the mat at a cheer competition, she is the picture of poise and confidence. However, that wasn’t always the case.

When Connors first signed up for the sport at the age of seven, she was shy and timid.

“Cheer allowed for me to make a lot more friends,” she says.

“I’m definitely a lot more outgoing now. I don’t really get nervous about talking to new people.”

The Bedford, N.S., high school student credits the sport for helping her step outside her comfort zone.

“Before I was pretty nervous to try new things and cheer kind of forced me to,” says Connors.

“It’s also taught me problem-solving skills and definitely resilience.”

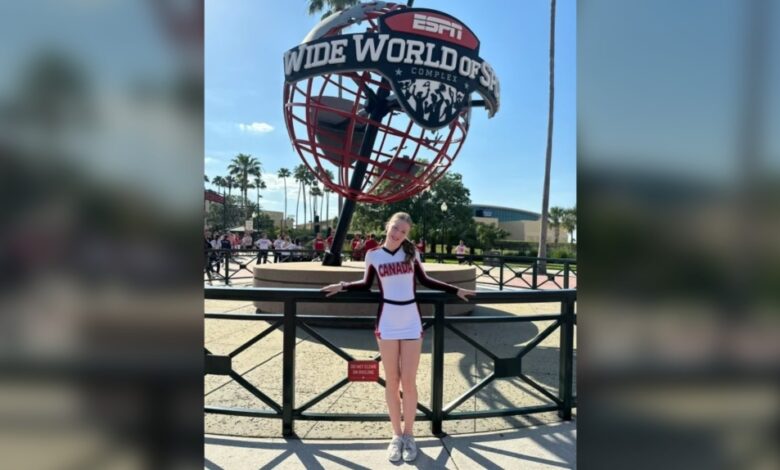

Hannah Connors is pictured in her Team Canada uniform in Orlando, Florida, where she participated in the International Cheer Union Championships. (Courtesy: Hannah Connors)

Hannah Connors is pictured in her Team Canada uniform in Orlando, Florida, where she participated in the International Cheer Union Championships. (Courtesy: Hannah Connors)

Building confidence

Allison Sandmeyer-Graves, the CEO of Canadian Women & Sport, says Connors’ story is not unique.

According to the organization’s 2022 Rally Report, 76 per cent of girls who participate in sports believe it helps build confidence and enhances their mental and emotional health.

“Sports equips people with these really valuable skills and experiences that they can use as scaffolding in their lives to get them to where they want to get to, whatever their goals may be,” says Sandmeyer-Graves.

“So, having women and girls have more access to those experiences and those opportunities to develop skills is going to set them up for greater success in whatever they choose to pursue.”

A player heads the ball during a soccer tournament in Owensboro, Ky., on Sept. 9, 2023, (Greg Eans/The Messenger-Inquirer via AP)

A player heads the ball during a soccer tournament in Owensboro, Ky., on Sept. 9, 2023, (Greg Eans/The Messenger-Inquirer via AP)

The benefits of sport

The benefits of sport are important for all children, but Sandmeyer-Graves says, right now, girls have less access.

“Of course there are intersections on that – there are boys from low socioeconomic communities, for instance, who would also face a lot of barriers – but girls are facing barriers because they are girls,” she says.

“Girls in our society overall are also less likely to be leaders and face gender barriers in so many different respects and so there is a broader social value to girls playing sports.”

Sandmeyer-Graves adds playing sports can empower girls and unlock opportunities for them in other parts of life where they are also being held back simply because of their gender.

“Just playing and accessing the same opportunities in sport and the same benefits in sports that boys have is the starting line, but it also has so much more meaning for girls because they have so much more distance to cover in society as a whole and sport can help them do that,” she says.

“It’s not just simply a matter of, it’s unfair within sport and we need to make it fair, it’s unfair in society and by making sport fair and ensuring girls have access to that, it’s going to help level the playing field in society more broadly.”

Beatriz, 13, skates on Girl Power Day, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on Aug. 4, 2021. (AP Photo/Marcelo Chello)

Beatriz, 13, skates on Girl Power Day, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on Aug. 4, 2021. (AP Photo/Marcelo Chello)

Providing opportunities

A life-long athlete and the operations manager at the Canada Games Centre in Halifax, Carla Alderson says she has learned many lessons through sports that have helped her in adulthood.

“I really do credit my confidence, my ability to collaborate, my ability to communicate in a way that can be understood by lots of different people from different backgrounds to sports,” says Alderson.

“I think sport definitely gave me the confidence to try other things. So, you excel in something, and it leads you to believe, ‘OK, well I can try something else,’ and that translates into professional life, or to schoolwork or into relationships.”

Alderson believes it is important to expose girls to sport when they are young – a time when she says they are most eager to try new things. And, as an adult who believes she’s received many benefits from sport, she is working to ensure the next generation is provided the same experience.

“I look at sport and the impact it has had on my life, and I am just so grateful for those opportunities,” she says.

Carla Alderson is pictured with her husband Neal Alderson and her daughter Marrin Alderson. (Courtesy: Carla Alderson)

Carla Alderson is pictured with her husband Neal Alderson and her daughter Marrin Alderson. (Courtesy: Carla Alderson)

Role models

Alderson and her friend Melissa Parker volunteer as coaches for a girls’ hockey team.

As a child, Parker played soccer and ringette, but struggled to continue in sports as an adult.

“For me, when I graduated from high school it was like sports were over. Organized sport to me was done because I thought it was U18 and that was it,” says Parker.

“Not knowing what my opportunities were, I kinda stopped being involved in sports.”

Parker didn’t get back into organized sport until she was in her 30s. One of the main lessons she hopes her players learn from their time together is you can continue to play in adulthood.

“I have had my players ask, ‘Do you still play hockey? What’s your league? What’s your team?’” says Parker.

“It’s nice for them to know that they can continue on. It’s another reason I coach, so that they can know that when your organized minor hockey ends, there are other options for you.”

Sandmeyer-Graves says girls who are active through their teen years are more likely to be active for life.

“So, there is a whole life picture component to this. It’s not just the moment of adolescence that we’re looking at,” she says.

Carla Alderson is the manager of operations at the Canada Games Centre in Halifax and a hockey coach. She believes the best way to keep girls in sports is to have more female coaches. (Courtesy: Carla Alderson)

Carla Alderson is the manager of operations at the Canada Games Centre in Halifax and a hockey coach. She believes the best way to keep girls in sports is to have more female coaches. (Courtesy: Carla Alderson)

Staying in sport

As coaches of an U18 team, Alderson and Parker say one of the biggest issues they face is player retention.

According to Sandmeyer-Graves, it is a common problem among that age group.

“Those teen years are where a lot of kids start dropping out of sport. It has a very gendered dynamic to it because our research shows that one in 10 boys, so 10 per cent, will drop off in that timeframe. One in three girls, so 33 per cent, will drop out in the same timeframe,” says Sandmeyer-Graves.

According to the Rally Report, almost half of parents (46 per cent) reported “low quality programming as a barrier to their 6 to 12-year-old girls’ ongoing participation in sport.” That number jumps to 55 per cent for girls aged 13 to 18.

The data in the report also suggests mental health concerns in youth are on the rise, for girls and gender-diverse youth in particular.

“Girls are under such enormous pressure at that age and there are so many things pulling them out of sports, but also just a real lack of societal reinforcement for girls playing sports. A lot of the messaging that girls consume from the media, from their social feeds, really fixates on what their bodies look like as opposed to what their bodies can do,” says Sandmeyer-Graves.

If a girl drops out in her early teen years, Sandmeyer-Graves says she is losing out on the benefits of sport during a tumultuous time in her life.

“At that age, they are really forming their values and identities and habits that they take into adulthood, and not having those wonderful protective factors of sport, the mental health component, the strong social sense of belonging, etc. in that period, it can really make that journey much more difficult,” she says.

“And the girls who are left behind have fewer girls to play with and against, which diminishes their experience and can lead them to leave as well.”

The snowball effect created by girls leaving sports also means they are less likely to grow up and become coaches or hold other positions of leadership in the sports system.

“Girls stay in sport because they feel accepted, because they form relationships, because they have a caring adult at the helm as a coach or somebody they can relate to, or somebody who respects them or who sees their abilities,” said Alderson.

In this Feb. 8, 2014, file photo, United States’ Christina McHale, right, talks with coach Mary Joe Fernandez during a break in a Fed Cup tennis match in Cleveland. (Source: AP Photo/Tony Dejak, File)

In this Feb. 8, 2014, file photo, United States’ Christina McHale, right, talks with coach Mary Joe Fernandez during a break in a Fed Cup tennis match in Cleveland. (Source: AP Photo/Tony Dejak, File)

‘Choice is imperative’

Even at the young age of 16, Connors is doing her part to encourage younger girls to participate. She was a coach in training for a couple of years, which led to her first official job as a coach.

When asked what advice she would give to parents who want their daughters to be involved in sports, Connors suggests allowing them to try different things.

“I know I did gymnastics, and I just didn’t enjoy it. I didn’t hate it, but I wasn’t excited for practice and I wasn’t really getting anywhere with it. As soon as I joined cheer everything completely switched,” she says.

Sandmeyer-Graves adds girls don’t want to be limited to sports that are traditionally seen as more feminine.

“There are girls who are just so excited to play rugby, who are just so driven to play football, who are driven to play hockey, which are sports that are more traditionally associated with boys and men,” she says.

“So, if we pigeon every girl into a very narrow band of sports because those are the ones seen as feminine, or suited for girls, what we’re going to find is that’s just not going to work for a lot of girls, and they are not going to play and get those benefits.

“Choice is imperative and I think that’s a really important message for parents.”

Nikki Anderson dives into second base in Kalispell, Mont., on May 24, 2012. (AP Photo/The Daily Inter Lake, Patrick Cote)

Nikki Anderson dives into second base in Kalispell, Mont., on May 24, 2012. (AP Photo/The Daily Inter Lake, Patrick Cote)

‘Believe you belong’

If girls in sport walk away with just one lesson, Alderson hopes it is the one she learned from Olympic hockey player Cassie Campbell.

“It is, ‘believe that you belong,’” says Alderson.

“Don’t go into a scenario thinking, ‘I don’t belong here, I’m not good enough, I’m not strong enough, I’m not fast enough, I’m not smart enough, I’m not pretty enough, I am not any of the enoughs.’ Just go in there and be like, ‘I believe that I belong,’ and sometimes you’ve got to walk that walk before you fully feel it on the inside.”