Credit card holders lost thousands after company deal, bank goes bankrupt

Constance McCall can’t catch a break.

The Edmonton woman needed to improve her credit score after getting divorced, so she signed up for a secured credit card that promised to help her do just that.

Instead, she lost thousands of dollars and left with a credit score worse than when she started.

McCall, 59, is one of many cardholders caught in a bitter legal battle between the credit card company and the bank it partnered with, Calgary-based Digital Commerce Bank, also known as DC Bank.

She applied for the visa through Plastk Financial & Rewards after seeing it recommended on Credit Karma, a website she trusted.

Plastk promises cardholders the chance to improve their credit scores by reporting their transactions to the credit bureau Equifax.

As a secured card, the credit limit corresponds to what customers pay up front for a security deposit — between $300 and $10,000.

Plastk says customers can cancel at any time and get their deposit back after a two-month retention period if the account is in good standing.

After canceling in December, McCall expected to get $4,500 back in February. Without that money, she had to borrow money from family and friends to pay for basic needs.

“It was extremely humiliating — $4,500 is no small amount, especially for someone like me. It’s huge,” she said.

“That would pay my next two months’ rent, buy my food.”

After Go Public brought McCall’s case to the company’s attention, Plastk refunded her deposit in full — four months after she was supposed to get it back.

Customers who signed up for a secured credit card from Plastk tell CBC Go Public that they lost thousands of dollars after failing to get their security deposit back, something the business owner blames on the bank he worked with.

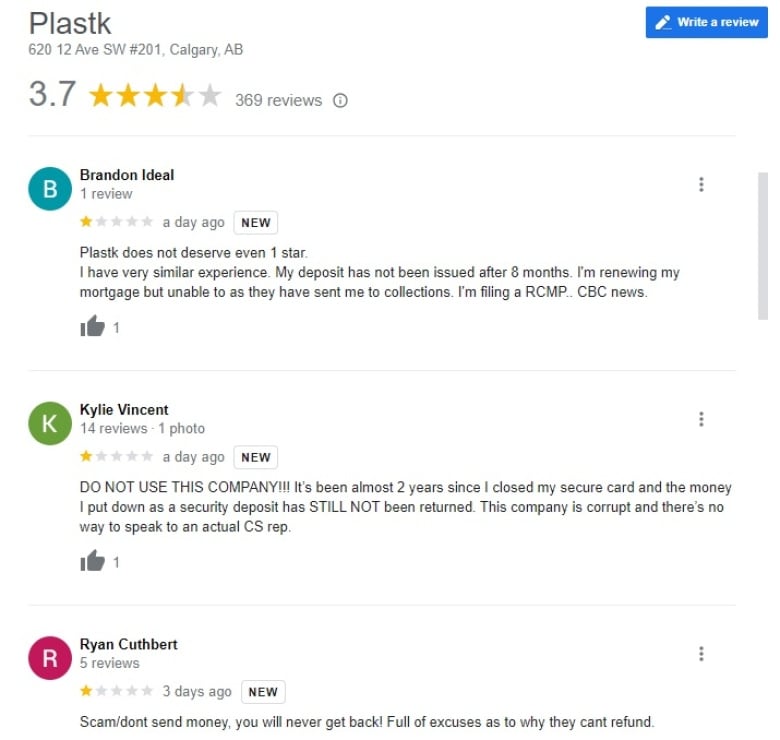

Plastk has 7,000 customers across Canada. Go Public spoke to a dozen — hundreds of others have posted complaints online — who say they too lost hundreds or thousands of dollars.

Gail Henderson, a consumer finance expert, says consumers using secured credit cards backed by non-bank lenders should be better protected.

Credit cards backed by bank borrowers are tightly regulated by the federal Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC), she says, but cards offered by non-bank organizations — such as Plastk — have fewer rules and are overseen by general provincial consumer protection departments. .

The FCAC warns consumers to “be careful when applying for a secured card from an unknown financial institution”, and recommends checking with the institution that the deposits are insured.

The agency says, in a report published in June, that complaints from non-bank consumers about financial products and services are resolved much less quickly than complaints about banks.

The FCAC report also said that most Canadians surveyed do not understand that financial products that are not backed by banks enjoy less consumer protection.

It suggested that oversight of non-banking products and services should be brought to the stricter level of federally regulated banks and credit unions.

Pedro Oliveira from Hamilton canceled his Plastk card on Feb. 12 and is still waiting for his $1,000 deposit. After about 100 days of not getting a fix with Plastk, he complained to the Better Business Bureau, then turned to the government – and was sent in a circle.

“I contacted Consumer Protection Ontario,” he said, “and they told me to contact the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, who told me to contact Consumer Protection Ontario.”

Brian Kline of Maple Ridge, BC, never received his card from Plastk after making a $2,500 deposit. At the end of October he asked to cancel his card and is still waiting for his refund.

He, too, reported to the Better Business Bureau and then to DC Bank, who returned him to Plastk. He then tried the Banking Services and Investment Ombudsman, who said the matter was not under his jurisdiction. He says the Better Business Bureau has closed his complaint as unresolved.

“Frankly, I have no confidence that my hard-earned money will ever be rightfully returned to me,” he said.

Plastk CEO and founder Motola Omobamiduro says he tries to refund customers, but their money is being held back by DC Bank.

Plastk and DC Bank teamed up in April 2020. Court documents show their dispute began about two years later when DC Bank said Plastk owed unpaid fees and failed to provide the required funds for the bank to pay Visa.

Plastk said the bank unfairly imposed new rules and fees and its technology didn’t always work, limiting Plastk’s ability to do business.

Plastk sued in January for $5 million and DC Bank filed a countersuit a few weeks later for $3.8 million.

McCall says the real shock was learning that the businessman behind Plastk is a former used-car salesman with a conviction for violating a consumer protection law.

On November 4, 2021, Omobamiduro pleaded guilty and was convicted under Alberta’s Consumer Protection Act for failing to pay liens on trade-in car sales, leaving his customers with debt.

Go Public spoke to two former clients, who say it ruined their credit scores.

Omobamiduro says he had nothing to do with the liens not being paid off; that it was the fault of an employee in BC

“It was an employee who did the deal. The partner should have flagged it and stopped it. Unfortunately, it went through and as a result I took responsibility,” he said.

Omobamiduro was ordered to pay a total of $22,993 in restitution to his car sales customers.

McCall says if she had known about the conviction, she would not have applied for a Plastk visa.

“I would never have put my own money into this person’s business.”

As for DC Bank, it says it is not part of customers’ credit agreements with Plastk.

“Plastk is the sole party responsible for this situation,” it said in an emailed statement to Go Public.

Visa Canada also takes no responsibility, saying through a spokesperson that financial institutions using the network have “responsibility” to their customers and for their business practices.

McCall says she didn’t know where to go – the whole ordeal was “mind-boggling”.

Go Public investigated and found a complicated web of government departments saying they can’t help and instead directing consumers elsewhere.

Service Alberta and Red Tape Reduction is the regulatory body responsible for Plastk’s secure credit card.

But when Go Public asked if it had received consumer complaints involving the company, or if the agency has taken action on behalf of consumers, it didn’t answer questions.

“One thing that is missing is a clear path for consumers when they have a problem [with non-bank secured credit cards]says Henderson, the financial expert.

“At the county level, more resources could be put into more proactive enforcement of the rules that are in place to protect consumers. I think there is also room to strengthen those rules and regulations… all Canadians deserve access to a safe and affordable credit card.” .”

Getting her money back was “a huge relief,” McCall said. “I can pay all the people I owe and take off my bank credit card. I’m still broke, but I don’t owe anyone anything.”

Meanwhile, Omobamiduro says he is working on another deal, planning to transfer his credit card company to another sponsor bank.

Submit your story ideas

Go Public is an investigative news segment on CBC-TV, radio, and the Internet.

We tell your stories, shed light on abuses and hold those responsible accountable.

If you have a public interest story, or if you are an insider with information, please contact GoPublic@cbc.ca with your name, contact information, and a brief summary. All emails are confidential until you decide to go public.

Read more stories by Go Public.