Expect more multi-residential buildings with smaller units, Halifax developer tells homelessness conference

Halifax is Canada’s second-fastest-growing midsize city, but what are the unintended consequences of population and economic growth?

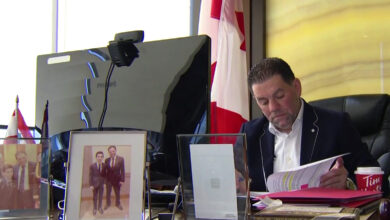

Expect to see more multi-residential buildings and smaller units, said Alex Halef, a developer who heads Banc Investments Ltd. and Inverse Developments Ltd.

“I know you’re seeing smaller units now, but even smaller still,” Halef said during a panel discussion Wednesday at the National Conference on Ending Homelessness.

“The issue is one of affordability. How many people can you put in a building? What is the rent you can charge?”

Rising costs and labour shortages all factor into the equation, he said.

‘Supply is not going to solve the problem’

“All you hear is supply is going to solve the problem,” Halef said. “I live this every day. Supply is not going to solve the problem. Actually, conceivably, if you overflood the market with development … cost will rise.”

It costs between $425,000 and $450,000 per door to build a multi-unit residential project in Halifax, he said.

If you borrow $375,000 for each unit at an interest rate of 4.5 per cent, that leaves a developer paying $18,744 a year in principal and interest a year on each unit, Halef said.

“That’s just to service your debt.”

Tack on operating costs including property taxes, utilities, management, repairs and maintenance, and “that’s another $6,500 (a unit) if you’re an efficient operator who is owning the buildings,” he said.

Add those numbers together and a developer is paying more than $25,000 per unit annually, he said. “And you haven’t earned anything yet on your equity.”

‘Levelled off’

These numbers have climbed between 35 and 40 per cent in the last three years, Halef said.

“Things have levelled off, but they’ve levelled off to where we are … now.”

Halef said he’d need to charge between $2,100 and $2,200 monthly rent just to break even.

“If you’re me, what should you earn as a return on your capital that you’re putting in – that extra $50,000-75,000 (per unit)? Do you want five per cent? Is it seven per cent? What’s worth the risk? That has to get added on top of the $2,100-2,200 in rent that you’ve got to capture just to pay your mortgage – principal and interest – and your debt.”

Removing barriers to density and various government fees would help the situation, he said.

“Every day you’re hearing about a new tax on people in my industry,” Halef said. “It’s not helping the situation as you can tell by the affordability issues.”

‘Tiny communities’

Developers are going to have to start looking at land differently, particularly on the outskirts of the city, he said.

“You see these tiny communities where you build 300 200-square-foot houses and you’re clustering them. That is a great solution out in the suburbs and in the rural areas where land is cheaper, and I think that that is an opportunity to provide some level of affordability from the development community,” Halef said.

Indigenous people need to be at the table for housing discussions, said Pam Glode-Desrochers, executive director of the Mi’kmaw Native Friendship Centre in Halifax.

“Extreme growth that we have seen in the city continues to marginalize my community,” she said.

“Affordable housing becomes harder and harder for us to access.”

Indigenous people need to work with developers so they can see themselves living in specific building projects, she said.

“Anybody who’s Indigenous knows that if you don’t have the exact number of bedrooms per child, DCS comes in and takes our kids,” Glode-Desrochers said. “Poverty is an issue, but we shouldn’t be penalized for those things.”

Land ‘seen as resource to make a buck’

Our relationship with land needs to change, she said.

“We shouldn’t be financializing land. It is going to be here long after we’re gone, and we need to start treating it differently,” Glode-Desrochers said.

“It is seen as a resource to make a buck and we need to treat it differently.”

Less than a decade ago, we were dealing with a shrinking population and folks moving west for work, said Stephan Richard, Community Housing Transformation Centre.

“And all of a sudden Nova Scotia was discovered just before COVID, and more importantly during COVID, which created a huge demand for housing stock,” Richard said.

“Despite … the development community’s best efforts to build at a record pace, supply is not meeting demand,” he said.

If we want to see the hundreds of people sleeping rough in tents get a roof over their heads, we need more housing, Richard said.

‘More community housing’

“In Nova Scotia, it’s less than three per cent of housing that is not owned by the private sector,” he said. “If we want a real, sustainable solution, we need more community housing.”

We need to ramp up capacity to build more supply, he said.

“But also provide the tools and resources to allow co-operatives and non-profit housing organizations to meet demand,” Richard said.

“The private sector has stepped up. We’re building at a record pace in Nova Scotia, in Halifax in particular. But we’re still not meeting demand.”

At least 20 per cent of homes here should be owned and operated by non-profits, he said.

“But we need both private and non-profit to be at the table and to be building the housing that people need,” Richard said.