‘I could have lost my child’: No ambulance available night Nova Scotia teen’s leg slashed open

It was supposed to be a night of celebration.

Cheryl Conrod-Baker’s oldest son had just gotten married and the reception unfolded as she hoped. Then she got a call about an hour after midnight. Olivia, her youngest son’s girlfriend, was on the line, distraught.

Her 17-year-old son Gabe was at home, cut badly, and Olivia didn’t know what to do. The young couple had been at the wedding and left around midnight. They got a cab to the family home in Head of Chezzetcook.

Before heading to bed, Gabe noticed the porch door was still open. He slammed the door shut and the double pane of glass shattered, sending shards of glass into Gabe’s leg.

Conrod-Baker, a licensed practical nurse for more than 35 years, told Olivia to call 911 right away. She told her to put a tourniquet on her son’s leg and elevate it, then left for home.

Olivia called 911. She got some bad news from the dispatcher: There was no ambulance, and the dispatcher didn’t know when one would arrive. Olivia and Gabe’s mother called three more times over the next three hours and got the same answer.

The family’s ordeal unfolded during the early hours of Oct. 22.

This is happening to more Nova Scotians, more often.

In September, Kim Adair, the province’s auditor general, released a scathing report. It said the ambulance service is in a critical state — short of staff and missing mandated response times for emergency calls and for patient transfers at hospitals.

Conrod-Baker said her son’s ordeal should be a wake-up call. But she’s worried that Nova Scotians have come to settle for an ambulance service that can’t do its job.

“I feel like, as a health-care professional worker, I have to speak out because I’m seeing things getting worse and worse. … People are dying in emergency rooms; people are dying at home because an ambulance can’t get to them,” she said.

“I could have lost my child. He could have bled out. It’s only because I’m a nurse and I know what I know that my son is OK.”

‘He was in shock’

When Conrod-Baker got home, she went to work on her son right away.

“He was in shock, bleeding badly and white as a ghost.”

She removed 20 to 30 shards of glass from his right leg. Some of the cuts were inches deep and required 20 stitches. She used contact lens solution to clean the wounds before bandaging them. On her third call to 911 she was advised by the dispatcher to take her son to the nearest emergency room at Twin Oaks Memorial Hospital in Musquodoboit Harbour, about 10 minutes away. She knew the hospital’s emergency department was closed the Sunday before but phoned ahead and found out it was open.

She arrived at the hospital at about 4 a.m. She said a nurse working in the emergency department was shocked by her son’s injuries and that there was no ambulance available. She would find out that one of the shards of glass came within an inch of the main artery in Gabe’s leg.

Why was there no ambulance available? There is an Emergency Health Services depot in Musquodoboit Harbour – 10 minutes away from Conrod-Baker’s home.

SaltWire spoke with a paramedic who’s based in a rural community in mainland Nova Scotia. The paramedic has 10 years of experience. She said ambulances as far as Cape Breton and Amherst are being called into Halifax, where they are overwhelmed with calls. That means at times there are no ambulances in many communities.

“Nine times out of 10 we go right into the city on Code 1 with lights and sirens on,” she said. We’re responding to an emergency.”

The woman asked that we not use her name out of concern of repercussions from her employer.

The main problem is the shortage of paramedics, and the main reason is money.

She makes $10 an hour less than an equally qualified paramedic in Ontario.

The situation is dire, she says. On one shift about a month ago, she was called into Halifax where they were short 16 ambulances. The staff shortage is so bad that ambulances are sitting empty at EHS bases throughout the province.

Gabe’s situation is not uncommon, she says.

“This is happening literally daily,” said the paramedic. “Someone’s died or they weren’t able to be treated in time.”

She said that in a case like Gabe’s, “anything more than 15 minutes is not acceptable.”

More calls, patient transfers

Adair said the average wait time for an ambulance in 2022 rose to 25 minutes from 14 minutes.

One reason is more calls. In the past five years there has been a 17-per-cent increase in 911 calls requiring an ambulance.

Another is patient transfers. In 2022, paramedics spent one quarter of every shift waiting in emergency department hallways to hand off their patients. That time alone adds up to $12 million.

She also said the province isn’t holding the ambulance service provider (Emergency Medical Care Inc.) accountable. Adair recommended the government penalize the provider for missing response times laid out in the contract.

The paramedic we spoke with said that the ambulance service shouldn’t be run by a private company. Ontario’s service is run by a not-for-profit corporation and is overseen by individual municipalities.

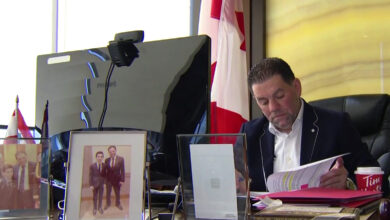

Charbel Daniel is executive director of provincial operations at EHS Operations, which oversees the private contractor.

He couldn’t talk about Gabe’s case because of health privacy legislation but said “the system was extremely busy that day across Nova Scotia.”

He also said improvements are being made, including paying for more staff to do routine patient transfers and stepping up recruitment.