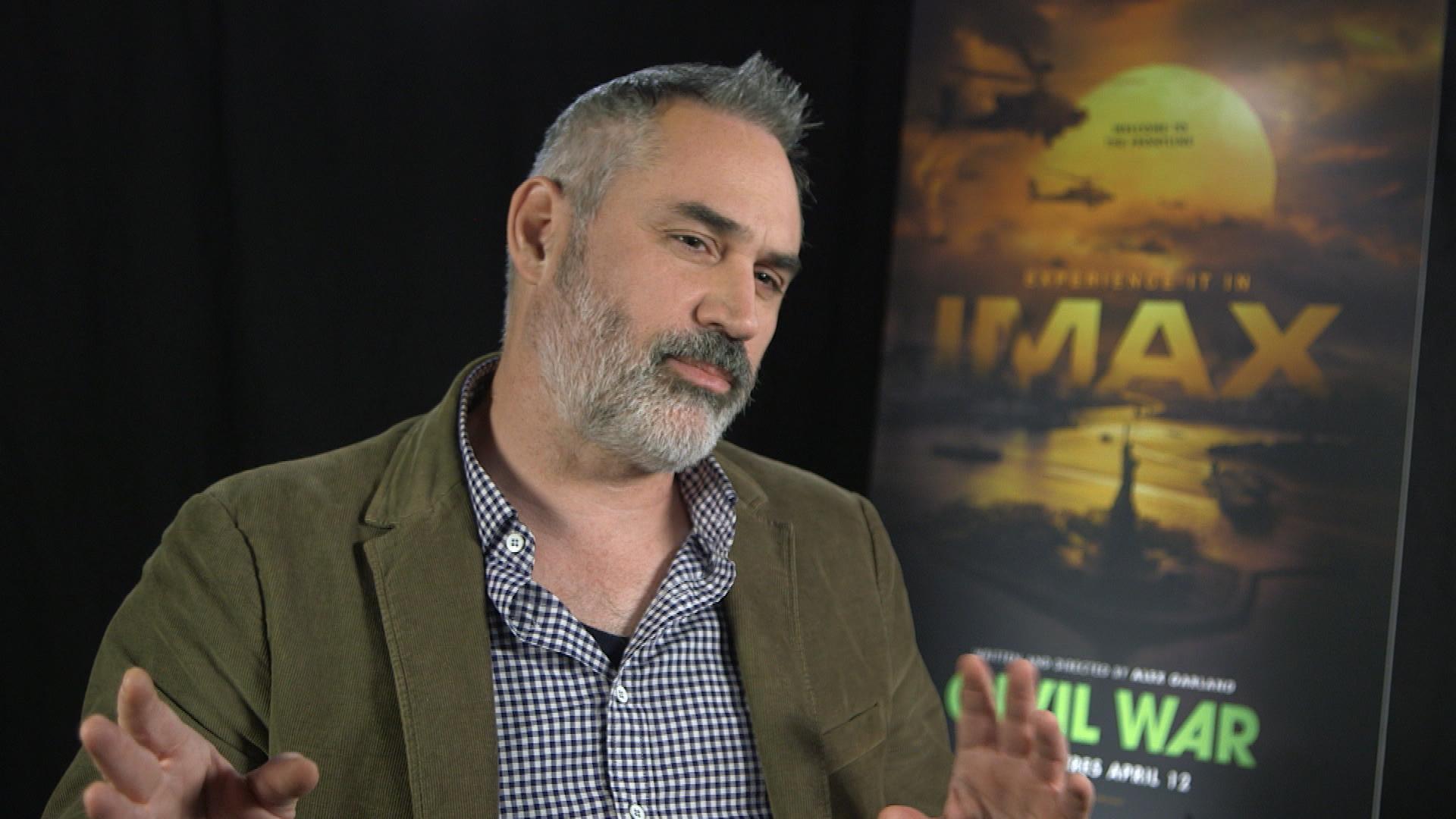

Q&A: ‘Civil War’ director Alex Garland on why writing female leads is less boring than writing for men

;Resize=(620))

The highly anticipated film Civil War lands in theatres this week. Acclaimed filmmaker Alex Garland (28 Days Later, Ex Machina, Annihilation, Men) wrote and directed the film, set in the imagined near future during a fictional civil war in the United States of America.

The film stars big-name talent including Kirsten Dunst, Jesse Plemons and Wagner Moura, and follows a group of journalists traveling through a U.S. war zone, attempting to document it with photos and arrange a big interview.

The film is being released ahead of a pause in directing for Garland, who will focus more on writing for the foreseeable future. Below is a conversation between Garland and senior entertainment reporter Eli Glasner. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Eli Glasner: You wrote this film [four years ago]. As you’re getting closer to us finally seeing the film, you start to see the direction the next U.S. election is going in, how did that feel for you as you saw these two things colliding?

Alex Garland: Uncomfortable. I think it’s complicated. That’s actually a really nuanced question, and in some ways, I think it’s undemocratic that the same choice arrives four years later. I think something should have shifted for lots of different reasons….

I’m left-wing. I’m a member of the Labour Party, which is the left-wing party in the U.K. For political health, every now and then, I would want my party not to win, because governments tend to get corrupt when they’re in power for too long.

And so, in those terms, to replay the same election feels really troubling to me. It’s really not about the individuals. It’s about the system and about what that represents…. In my country and in America, and several European countries and other places, Middle East, Asia and South America, there is a really serious and very strange problem with social division and populist politics, which thrives on that division and encourages it and a drift toward extremism.

EG: I think part of what makes this film so conceivable is that you use things that are taken from an America I recognize. I mean, that helicopter with the burned-out JC Penney sign in the background, the stadium … how difficult was it to find scenes like that working in America?

AG: It’s not very hard at all, because America is just like any other large state. I think this is something often people don’t understand. If you live in the West, you understand it. From the outside, of course, the West can look so wealthy in a way, just so wealthy, which of course it is, but the wealth is concentrated. It’s not broadly spread. And there are areas of really extreme poverty in America, and in my country, too, and in all of these Western countries.

And of course, that’s the engine of some of the anger — people say, “When is a government gonna do something about us?”

Alex Garland tells CBC’s Eli Glasner how Jesse Plemons came to star in his new dystopian epic Civil War.

EG: I’m gonna switch to your amazing main character, Lee. I look at your films — again and again, you seem drawn to writing and telling stories about women, which is not that easy a thing for every writer to do. I wonder, is this just happenstance, or something that you actually work on? Because Lee could have been a man, right?

AG: Yeah, she could have been. Honestly, I think that’s for two reasons. One is, I’m not really sure how one differentiates between men and women, anyway, and in all sorts of different ways.

But, I was born in 1970, I’m in my mid 50s. In the period of time I grew up and was watching films, every film pretty much had a male lead. And … it’s not really a political act on my part. It’s actually just faintly boring to write it as a guy because that’s all I used to see. So in some ways, I’m sitting down to write this story, and I could write Lee as a bloke, or I could write him as a woman, and I just feel very slightly more bored by the idea of him being a man.

WATCH | Alex Garland on casting Jesse Plemons in Civil War: ‘That wasn’t a choice’: MEDIA]

EG: I have to ask about that scene between Kirsten Dunst and Jesse Plemons [who are married in real life]. What an interesting choice to bring him in.

AG: That wasn’t a choice. There was another actor who was going to do it. Well, he bailed just before we were about to start shooting.

I was standing on the street, and he called me and said, “I’m really sorry. I can’t do it.” And I was obviously very polite and said, “Of course, I understand.” But inside I was thinking, “Oh my God, we’re completely screwed.” I hung up … and was walking into rehearsal with the actors. And I thought, “Oh, I should tell them, because they were expecting to work with this guy. It’s the right thing to do.”

And Kirsten said, “Well, what if I asked Jesse?” And I said, “Do you think he’d do it? Great!” And I think he’d already read the script because she was gonna do it. It’s in my memory, like, she just called him, said, “Do you think you could do this?” And 24 hours later, it was Jesse.

EG: What’s it like to see how close they are as partners on the day [shooting that scene]? That is a fearsome scene, and I just wonder what that was like, to see them go from people who love each other to antagonists in front of your camera?

AG: You know, they were just being pros and doing their thing. I do remember on the day they kind of kept distance from each other. They weren’t really hanging out. In fact, Jesse, I seem to remember, was keeping his distance from everybody except the other soldiers that he was working with, which I can understand. When you see the scene, that sort of makes sense.

EG: How do you make a movie about war without falling into the kind of glamourization, romanticization, the adrenaline-fuelled experience we have so many times of seeing war on the big screen?

AG: We were just careful. I should always, implicitly, I hope, acknowledge that it’s a large group of people making a film. Film is really a product of a conversation. I know it gets presented as, like, a director. It’s not really. And we talked about it a lot. We thought about it. We deliberately tried to avoid taking cues from cinema in some respects and more took cues behaviourally, or action, or sound from either lived experience or documentaries or news footage, and really tried to adhere to that.

EG: Is it a warning? Are you kind of putting this out there as a bit of “Caution: Road ahead”?

AG: Well, I think yes, but I’m a little bit allergic to the “I” bit of that sentence. Because my memory of four years ago, when I wrote this, is the anxiety and the frustration with public discourse and polarization and populism, and all of those things, was shared.

I’m left-wing. I have very good right-wing friends. What we’re arguing about is things like how tax is used or whether you have free markets or regulated markets. It’s that sort of zone. But, somehow, we are expected to start hating each other, or take it away from, “This is a right argument or a wrong argument,” but make it into, “You as an individual are good or bad.” And there’s something about that which is just really stupid. It’s really flat-out stupid.

So I felt alarmed about that. I felt angry about it and felt there was a lot of other people who felt exactly the same. The strange rage states are occupied by polar extremes. It’s just they’re very loud. They have voices, and they use their voices and they bully and intimidate in a particular kind of way. And I thought, “Fuck that, you motherfuckers.” That’s what I thought.

Civil War filmmaker tells CBC’s Eli Glasner, ‘It’s actually just faintly boring to write it as a guy.”