The 2023 housing crisis can still be solved the Expo 67 way

“An insanely insane example of criminal naivete.”

That’s how Paul O. Trépanier described Habitat 67, a strong contender for the title of Canada’s most iconic building. He was an architect by trade, but at the time served as mayor of Granby, Que. Granby’s growth in the 1960s.

If you’re old enough to remember Expo 67, chances are you remember it was a huge party where seemingly the whole world came to Montreal to celebrate Canada’s centenary. That’s right, it was an international ‘happening’ during the Summer of Love, which attracted 55 million visitors. What is less appreciated is that Expo was also a demonstration of how people might live in the near future.

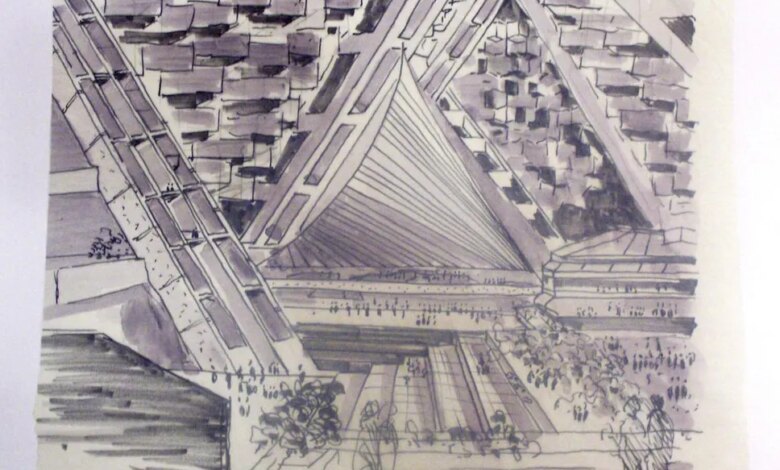

As originally envisioned, Habitat 67 would be a massive mixed-use urban area with some 1,200 homes, along with all the amenities such a community could need – office space, schools, small businesses, etc. Massive A-frames would stacks of residential modules, stepped back floor by floor, protecting the common public spaces below. The accommodation units are arranged to provide maximum privacy, sunlight and a private garden.

It is difficult to adequately capture and convey the monumentality and significance of master architect Moshe Safdie’s original plan; Habitat was nothing short of a housing revolution.

Fortunately, technology now gives us a very clear picture of what it would have looked and felt like. His company, Safdie Architects, has partnered with Epic Games and Neoscape to create a virtual three-dimensional model of the project using the first Unreal Engine 5, the advanced graphics platform behind the latest version of “Fortnite” and more.

It’s a far cry from how the original concept (Safdie’s graduate project at McGill University’s architecture school) was developed, drawing everything by hand and building a huge model from hand-carved wood blocks. The development of Lego – new then, in the mid-1960s – was a big step forward, as his design team could envision the housing modules in different configurations. (Ironically, Lego refused to produce a Habitat 67 model kit several years ago, despite enthusiasts en masse recommending it.)

The building that was finally completed is actually only a small part of the original vision. Built on a section of Mackay Pier in Montreal’s Old Port that was too narrow for the larger A-frame structure, it nevertheless incorporated the same basic elements of the original so that it would serve as a functional proof of concept.

The genius of Habitat is that it addresses all the big problems with high-density urban housing, problems that have plagued North American cities for half a century since then. Safdie’s solution to the urban housing problem almost amounts to doing the exact opposite of most of the dominant trends of the time, trends that continue maddeningly to this day.

Post-war residential development in North America primarily took two forms: suburban detached single-family homes and high-density urban residential towers, often grouped together in what has been called a “towers in a park” arrangement. Most of Scarborough is a good example of the former, while St. James Town is an excellent demonstration of the latter. You’ll find examples of both in almost every North American city, and they all suffer from the same problems that were as apparent to Safdie in 1967 as they are to the ever-increasing number of Canadians for whom owning a home seems as likely as winning. the lottery.

However, low-density suburban development can only go so far, before a city runs out of land and commute times become unsustainable – and increasing suburban density is a hard sell, as the allure of the suburbs demands privacy and green spaces. spaces is to call your own. Furthermore, low-density suburban development is neither prudent nor desirable in the climate crisis era, especially given Canada’s troglodytic approach to public transportation development.

The other end of the spectrum, at least in the 1950s, involved razing entire sections of a city and then building many high-density residential towers, often visually indistinct from each other and extraordinarily close to each other. While the intention may have been to build towers in a park, the profit motive often encouraged developers to forego many of the green spaces, as well as nearly all the services such high-density housing sectors might need. Across North America, housing projects like this quickly became undesirable to the white-collar middle class for which they were intended, and instead became housing for the most marginalized.

Most modern high-density urban housing still suffers from these problems, the main difference being that people today pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to own apartments that are smaller than those that used to rent for only a few hundred a month. Despite the option of better furnishings and fixtures, or high-end equipment in a shared gym, high-density residential towers offer almost no privacy and little more than a breezy balcony as a possible “green space.” In far too many high-rise condominiums in downtown Toronto, there’s no view of anything but the nearly identical apartment block or office building across the street.

Habitat offered an alternative to the problems inherent in both trends. Unlike apartment towers, where residents share the same front door, row of elevators, hallways, and (generally few) common areas, Habitat’s housing units all had individual private entrances that could be accessed in a variety of ways. The housing units were assemblies of prefabricated modules – built on site – that could be connected and combined to produce a variety of houses of different shapes and sizes, each with their own unique perspectives on the city. The spacious sun and individual gardens are possible thanks to the withdrawn design.

These design elements, which emphasized the privacy and closeness to nature that suburbanites sought, were balanced with design elements intended to foster a close-knit sense of community in a densely populated urban environment – elements largely inspired by Safdie’s Israeli childhood home in Haifa. .

A network of walkways, community gardens and common areas would provide ample opportunities and spaces for neighbors to get to know each other, not to mention safe environments for children to explore. The ubiquitous automobile, such a status symbol for the middle class of the mid-1960s that most North American cities were radically rebuilt to accommodate them, was conspicuously absent from Habitat. The vast interconnected networks of living and working spaces were completely separated from vehicular traffic.

Cars were also conspicuously absent from many of Expo’s fairgrounds – a deliberate choice prompted by the need to quickly and efficiently move millions of people around the fairgrounds, as well as a growing social awareness of the negative environmental, environmental and economic impacts of widespread car use. In the mid-1960s, it seemed obvious that the inhabitants of future cities would probably not travel in their own cars, given the pollution, congestion and disproportionate amount of space required for parking infrastructure.

That Safdie’s original vision was not completed is not due to any impracticability of the design: at a time when people were flocking from the big cities to the suburbs, Habitat quickly established itself as one of the few sought-after downtown addresses.

The lesson here is not only that a 60-year-old Brutalist masterpiece may hold the key to solving Canada’s housing crisis, but that the federal government needs to take a more hands-on approach to solving the interconnected crises plaguing our cities. This is as much a problem of housing access and affordability as it is of plans to radically reduce cities’ carbon footprints, improve traffic flow and public transport, improve access to vital social services and, above all, enhance the urban experience. and quality of life. Habitat 67 still offers viable solutions to all these problems.

Both the most successful World’s Fair of all time and, arguably, Canada’s most recognized and distinctive building, were created with the intention of envisioning how people might live in an ideal future city. Government-funded collaborations created innovations that the private sector has definitely not pursued and built upon. And yet, rather than let these accomplishments guide us, we’ve largely treated them as odd curiosities whose success was entirely accidental.

Now that we can see that what could have been still appeals to us, we might want to think about rethinking it. The past is never dead. It’s not even over.

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2023/06/18/our-housing-couldve-been-beautiful-it-can-still-be-how-expo-67-shows-us-a-way-out-of-2023s-problems/sketch.jpg)

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2023/06/18/our-housing-couldve-been-beautiful-it-can-still-be-how-expo-67-shows-us-a-way-out-of-2023s-problems/newsweek.jpg)

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2023/06/18/our-housing-couldve-been-beautiful-it-can-still-be-how-expo-67-shows-us-a-way-out-of-2023s-problems/waters.jpg)

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2023/06/18/our-housing-couldve-been-beautiful-it-can-still-be-how-expo-67-shows-us-a-way-out-of-2023s-problems/habitat_overhead.jpg)

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thepeterboroughexaminer/news/peterborough-region/2023/06/13/green-team-hits-the-streets-again-to-beautify-downtown-peterborough/greenteam.jpg)