Art tech start-up replicates original art pieces through robotics

A Canadian robotics company is changing the way painters share their artwork.

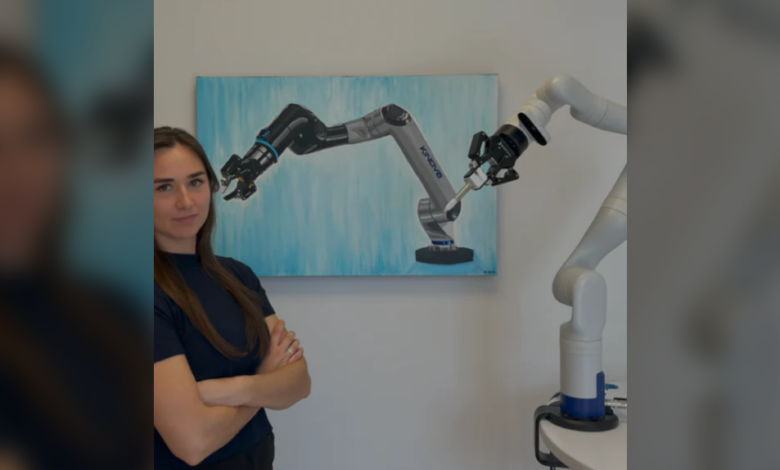

Acrylic Robotics, an art-tech start-up based in Montreal, is using robotics and artificial intelligence for visual artists to reproduce their artwork at scale.

Chloe Ryan, the founder and CEO of Acrylic Robotics, said she started this company out of a realization.

“It was realizing that basically every single other art form has some way to reproduce it at scale,” said Ryan, who has a background as an independent artist and who studied mechanical engineering at McGill University.

Writers, she pointed out, are no longer recopying manuscripts by hand. “Everyone could access their literature.” But this is not the case for painters, with the full magnitude of an artist’s intention restricted to original copies.

At first, Ryan built a robot that would help her paint faster.

“I realized if I could build this for myself I should be making it accessible to all artists,” she told CTVNews.ca. “That’s when things changed into me thinking I could make an actual company out of this.”

Ryan’s innovative direction, she said, started with a question: “How do we make painted art at scale, in support of independent artists, while making fine art more accessible?”

The answer to this question came in the form of a digital system where artists can track all their brush strokes digitally. “Anyone with a laptop or tablet could use it, anywhere geographically,” Ryan said.

After brush stroke data is uploaded to this digital system, Ryan said Acrylic robots are then able to emulate the original painting with paint brush attachments.

“Instead of making just one original artwork and selling it for $5,000 or more, we could offer a limited edition collection at a lower price point for a more accessible audience,” she said. “Artists could still generate the same income.”

Ryan demonstrated her robotic technology at the Hardware Tech and Founders Showcase, an exhibit in Toronto, hosted by founder-support organization Journey, on Thursday.

At Acrylic’s display, a robotic arm with a paint brush attachment mechanically stroked a blank canvas, reproducing an image based on digital files.

Two robotically replicated paintings were shown on the table before it – both an image of a lion’s head, originally by Toronto-based artist Matt Chessco, who partnered with Acrylic for a pilot project.

For the most part, both paintings were virtually identical. But a closer look would reveal slight, nearly imperceptible discrepancies in certain brush strokes. This, Ryan said, is part of the project’s charm.

“When I first started the company, I assumed we had to get 99.9 per cent perfection or our artists would hate us,” she explained. “A lot of the research that we did, both quantitative and qualitative, found that artists actually want there to be a certain degree of imperfection.”

Ryan pointed out that each robotic replica should not look completely different from the original piece, but that, if each artwork is slightly different, “people will pay a lot more because it’s a slightly unique piece, and it feels more meaningful than something mass produced like at Ikea, for instance, where every single thing is completely the same.”

Because of the ways the paints mix, and the ways that the brush dips, there’s always going to be a tiny inconsistency, she explained, but there is a limit to these imperfections.

“We have quality assurance,” Ryan said. “We also sometimes remove some from what we release. Macroscopically the goal is to have them all be completely identical.”