Fixed-term leases that let Nova Scotia landlords avoid rent cap rules are popular and legal, but are they fair?

When Bridget moved into her north end Halifax apartment in late 2020, she thought it would be her final long-term stop until she could afford a home of her own. She settled in over the next three years. Living close to Fort Needham Park, with its wooded trails and views of the Narrows, she could walk to the shops in the Hydrostone. Trees canopied the neighbourhood streets, filled with clapboard bungalows and modest post-war homes.

“I moved [here] six months into the pandemic,” Bridget says, speaking by phone with The Coast. “This was a place where I found a lot of security at a time that was really uncertain. I was able to live alone; I was able to afford to live alone—and really stake a claim on a space that felt like mine while things were kind of in chaos everywhere else.”

She did what she could to preserve it. She paid her rent on time. Lived quietly. Had a good relationship with her landlord and property management company—or so she believed. That changed, she tells The Coast, with a single email. In April, Bridget received a notice from Ansell Property Management: Rather than extending her fixed-term lease, as her landlord had done for two years running, she would need to leave her apartment by Aug. 31.

“This notice is being issued to all tenants residing in properties operated by your landlord in the Halifax Regional Municipality,” the notice read. “It is not a reflection of our appreciation for your tenancy.”

Martin Bauman / The Coast

More than two in five Haligonians rent their homes, according to the latest census results. That outpaces the national average of one in three.

The notice came as a surprise to Bridget. “When I moved in, [I told] the property manager, ‘I would like to live here a long time.’ And they seemed very on board with that.” (The Coast has agreed to keep Bridget’s identity private, out of her fears that speaking publicly could jeopardize her future tenancy prospects.) Suddenly, she found herself re-entering a rental market with historically low inventory and soaring rental rates. So, too, did tenants of nearly 60 other rental units across the HRM who shared the same landlord, The Coast has learned. It would push Bridget’s budget into uncomfortable terrain.

“I keep using the word ‘unhinged,’ but that’s how the rental market feels right now,” Bridget says.

It’s not a unique situation in Halifax. It’s not an illegal one, either—no rules or bylaws were broken in Bridget’s eviction. But it’s one that affordable housing advocates and MLAs alike have been calling on Nova Scotia’s government to put a stop to in the midst of a provincewide housing crisis. And as the number of unhoused Haligonians eclipsed the 1,000 mark in August, it’s an issue that has sparked debate between tenants, landlords, property managers and politicians about who’s responsible for the region’s housing woes—and how the HRM is grappling with a growing population and not enough places for everyone to live.

‘Homeownership is completely out of reach to me’

To understand real estate in Nova Scotia—and, at least by some accounts, one of the causes of Halifax’s housing affordability crisis—it is useful to understand two truths: Halifax is a city of renters, and Nova Scotia is a province of property investors. As of Canada’s latest census, more than two in five Haligonians rent their homes. (The national average is one in three.) And nearly two-thirds of homes built in Halifax between 2016 and 2021 were occupied by renters in 2021—more than in any municipality apart from Quebec City. On the opposite end, Nova Scotia has one of the highest rates of investment property ownership in all of Canada: According to new data from Statistics Canada, nearly one-third of homeowners in the province in 2020 owned at least two properties—and the wealthiest 10% of owners with multiple properties controlled a quarter of all residential properties in the province.

That divide is one that has sparked no shortage of conflicts between tenants and landlords: As the cost of housing has soared across the HRM, it has left homeownership a distant reality for a growing share of Haligonians—Bridget among them. A 2022 RBC report on housing affordability found that for Haligonians to qualify for a mortgage on a benchmark-price Halifax home last fall ($577,700) required a household pre-tax income of $116,415. As a freelancer in Nova Scotia’s film industry, Bridget makes anywhere between $40,000 to $48,000 a year—a figure that puts her above the median provincial income of $36,400, but well below the means required to buy a home.

Martin Bauman / The Coast

A 2022 report found that for Haligonians to qualify for a mortgage on a benchmark-price home required a household pre-tax income of $116,415.

“I’ve been living in this survival mode for years, and I know a lot of people who have been too. It’s a shitty way to live,” she tells The Coast. “And 1695177618 I mean, financially, homeownership is completely out of reach for me.

“I think we’ve lost our way as a society,” she adds. “There’s this hyper-individualistic bent to [everything] now. It’s like, ‘Well, if you can’t make it yourself, you’re not trying hard enough.’ Well, everyone I know is trying incredibly hard. And we have these circumstances where people—despite trying as hard as they possibly can—are still not able to thrive.”

‘The ultimate escalator to wealth’

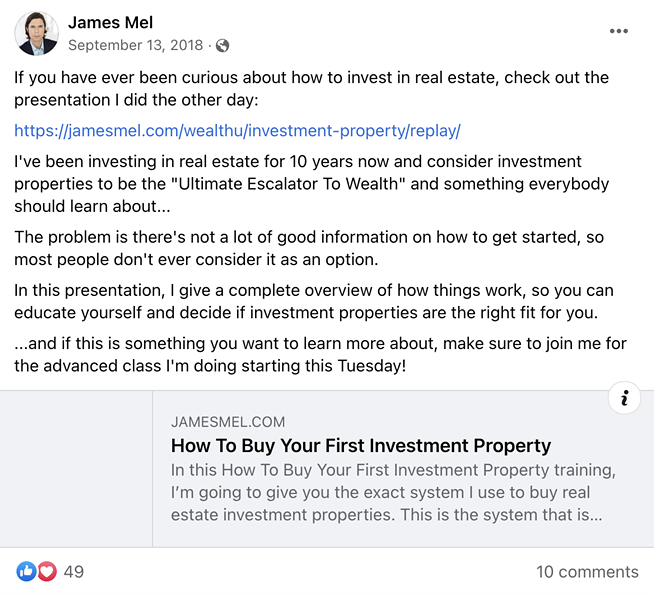

Bridget knew little about her landlord during her three years living at her apartment. She had heard that he was living in British Columbia. Mostly, she dealt with Ansell Property Management—the company would get in touch, year after year, asking if she would like to renew her lease. But she knew she wasn’t her landlord’s only tenant. Land registry records show her building is owned by Pineapple Properties Inc.—which in turn, a search of Nova Scotia’s joint stock companies registry reveals, is helmed by James Mielnik. But Pineapple itself has little else in the way of public records: The company has no website.

The Coast reached out to Mielnik through several avenues for comment, but he has not responded. Mielnik’s public Facebook page lists him as a virtual coach who helps “regular people escape the 9-5 by building a real estate portfolio.” In a 2018 Facebook post, Mielnik writes that he sees investment properties as the “Ultimate Escalator to Wealth” and “something everybody should learn about.” In another post from 2021, he celebrates a “huge milestone,” claiming to have closed on his 26th property—bringing his total real estate portfolio to 102 rental units, he adds.

James Mel / Facebook

A public Facebook post from James Mielnik in 2018 describes investment properties as the “ultimate escalator to wealth.”

The Coast has identified 21 buildings—ranging from bungalows to 12-unit apartment buildings— across Halifax owned by Pineapple Properties Inc. Sixteen of those are leased to tenants through Ansell Property Management. A Coast review found 59 units rented out through those properties. When The Coast reached Ansell’s owner, Gillian Ansell, she declined to confirm exactly how many of Pineapple Properties’ tenants received the notice of non-renewal that said it was “being issued to all tenants residing in properties operated by your landlord”—she says “that’s a privacy thing”—but stressed that in many cases, her company has tried to find tenants other places to live.

“We’ve moved tenants from one property to another property. We’ve [done] everything that we can to try and minimize its impact,” she tells The Coast. “I’ve given some people an extra couple of months on a fixed lease here and there when they’ve been struggling to find a place and said, ‘OK, we’ll give you another two months or three months until you find somewhere that’s suitable for you.’”

The fixed-term lease debate

Following the mass eviction, it isn’t clear whether Mielnik intends to re-list the properties with new tenants, sell them, renovate them, demolish them or leave them empty. (The Coast has asked Mielnik about his plans, but has not received a reply.) All are legal avenues. Nova Scotia’s Residential Tenancies Act permits any of the above in the case of a fixed-term lease ending—which Bridget sees as part of the problem: There aren’t enough protections, she says, to keep tenants housed in a city with a 1% vacancy rate and rents that have increased at among the highest rate of anywhere in Canada in recent years.

“Look at the homeless population now. Making it more difficult than it already is for people to find housing is just pushing more people out of shelters and into the streets,” she tells The Coast. “I might be fine, but there’s someone in my building who I’m certain is on income assistance, and I have no idea where he’s gonna go.”

“I might be fine, but there’s someone in my building who I’m certain is on income assistance, and I have no idea where he’s gonna go.”

tweet this

Nova Scotia introduced a temporary 2% rent cap in 2020, in part to address this problem. But Bridget argues the way fixed-term lease legislation is written gives landlords an incentive to shuffle through tenants in order to skirt the cap—a complaint The Coast has heard from numerous other tenants and legal advocates in recent months. That’s because of how the fixed-term leases differ from periodic leases: Unlike the latter, which roll over when they reach their term end (say, at the end of a month or year), fixed-term leases don’t—which means tenants are left without any security of tenure. And while Nova Scotia’s current rent cap holds landlords to a 2% increase if their tenant remains the same from one year to the next (at least until Dec. 31, after which the cap will rise to 5%), there are no limits on rent increases between tenancies. A landlord could end one tenant’s fixed-term lease of $1,000/month and re-list their unit for $2,000/month.

Martin Bauman / The Coast

In August 2023, the average monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Halifax reached $1,909, according to Rentals.ca.

“I don’t think the power to terminate a lease should fall in favour of a landlord when they can financially gain an enormous amount from it,” Bridget says.

To be clear, The Coast has no evidence that Pineapple Properties is ending its tenants’ leases to circumvent Nova Scotia’s rent cap. (We asked Mielnik what prompted the decision to end his tenants’ leases, but have not received a reply.) But it’s the system that encourages landlords to skirt the cap—regardless of whether they do—that Bridget and other tenants take issue with. It’s the same scenario that left Evan Walker and his family “blindsided” earlier this year, when his landlord opted to raise the rent on their Southgate townhome from $2,200 a month to $3,195 per month—a price they simply couldn’t afford.

“At some point, there has to be some sort of intervention,” Walker told The Coast in June. “We ended up getting burned by a damn loophole.”

Ansell sees the matter as more nuanced: With shelter costs up 4% from last year, per Nova Scotia’s Finance and Treasury Board, she argues the province’s rent cap is too restrictive for landlords to account for the added costs they’ve incurred. If owners are paying a variable mortgage, property taxes and heating bills, all of those costs could exceed what they’re able to recoup in the form of rent.

“What can you do when the government imposes a 2% rent cap and subsequently drives [expenses] up all across Nova Scotia when the cost of oil, power, property taxes, mortgage rates, everything else has increased by way more than 2%? And a landlord isn’t even allowed to impose a reasonable increase?” she asks. “The cost of living has skyrocketed, and that is the same for landlords and tenants.”

That rings hollow to Bridget.

“I understand that everyone is dealing with rising costs… but when you’re looking at companies [that] own dozens of buildings [and are] taking half of someone’s income every month to line [their] own coffers,” she says, “I mean, I’ve lived in houses and known that I’m paying someone else’s mortgage instead of my own. And that’s hard.”

A lack of housing supply

It’s not hard to understand the appeal of property investment: In the last 20 years, it has been among the surest forms of amassing wealth in Canada. (Not that it’s bound to stay that way.) As pensions have disappeared from Canada’s workplaces, wages have stagnated and full-time jobs have been replaced by temporary contracts, more Canadians are turning to housing as one of their biggest sources of retirement savings—as long as they can afford it. And nowhere is the shift to housing as investment properties more prominent than in the Maritimes—where, until recent years, housing was still cheap.

Martin Bauman / The Coast

Nova Scotia is not building enough housing to accommodate future growth, its deputy housing minister said in May 2023.

That might be fine if Nova Scotia’s housing supply outpaced the province’s population, but the reality is far different. In May, Nova Scotia’s deputy housing minister, Paul LaFleche, claimed the province needs “in the order of 70,000-odd units… in the next five years” to meet housing demand. As of July, the province was on pace to see roughly 5,800 new homes built in 2023, per Nova Scotia’s Finance and Treasury Board. Even if Nova Scotia were to double that pace for five years, by stroke of miracle or “go like hell” gumption, it would still fall short of the province’s needs.

“Right now our estimate, which we haven’t released, is that we have in the order of 70,000-odd units needed in the next five years to support the population in Nova Scotia. That’s going to have to be all sorts of different units from affordable to mid-level to higher end.” – Paul LaFleche

tweet this

It is with this reality in mind that Suzy Hansen, MLA for Halifax Needham and caucus chair of the Nova Scotia NDP, introduced a private member’s bill in March this year. She’s proposed to amend Nova Scotia’s fixed-term lease legislation so that landlords would need to give tenants the opportunity to extend their fixed-term leases as month-to-month leases—which offer tenants stronger protections—when they’re set to expire.

“Folks have to move regularly, which—in this time—is a troubling situation when we don’t have the housing market to hold them,” Hansen says, speaking by phone with The Coast. “Like everything with a balance, there’s a use for [fixed-term leases]. But in this case, because we are in a housing crisis and we have a 1% vacancy rate, people need to have an assurance that they’re going to be able to live in the home that they’ve lived in, year after year, with an option [to stay].”

It’s not a panacea: For landlords, month-to-month leases can make it hard to evict problem tenants; but Hansen counters that enough legal avenues remain through the Residential Tenancies Act to handle those issues when they arise. For the MLA, keeping people housed takes precedence—Hansen says her party was receiving calls “every single day, maybe five or six a day,” where tenants would share their fears about fixed-term leases not being renewed, or landlords evicting tenants only to raise the rent by hundreds of dollars:

“We’ve heard of hundreds [of cases]. And we say this because when we sat in Legislature, we brought it up to the minister [Colton LeBlanc]. And the minister said he only received nine calls, or nine cases [involving fixed-term lease complaints].”

Hansen’s bill passed first reading on March 21, 2023. Despite support among housing advocates, it has not returned to the House of Assembly since—“if we put it forward to another reading, it risks being shut down immediately,” she says. The reality of any level of government: It is rare for opposition members’ bills to pass.

In an emailed statement, a spokesperson for Service Nova Scotia minister LeBlanc—who also oversees the Residential Tenancies Act—tells The Coast that the province is “always looking at ways to strengthen the Residential Tenancies Program while balancing the needs and interests of both tenants and landlords,” and that tenants should “understand what they are signing when they enter any type of lease.”

Bridget says she doesn’t know any renters who aren’t on fixed-term leases anymore. Two Halifax property management companies The Coast has spoken to, including Ansell’s, say fixed-term leases are “almost exclusively” the norm in today’s rental agreements.

Ansell herself feels at a loss for an answer to solving the HRM’s housing crisis:

“I don’t know what the solution is, but everybody’s got to come to the table, and everybody’s got to be prepared to give something.”

‘Nobody wants to move every six months’

Three weeks ago, Bridget moved into a new Halifax apartment. Some things are the same—she’s on another fixed-term lease—while others are different: She has a roommate now. Despite that, Bridget says, her share of the rent is higher than when she lived alone—“which is indicative of where the housing market is,” she adds. “That’s been an interesting adjustment to wrap my head around.”

She’s had a lot of time to think about housing, and belonging, and the future of where Halifax appears to be headed. She worries about what’s to come. She fears for the families whose stories she encountered while scrolling through Facebook groups in search of apartments—people asking for spare tents or places to couch surf or affordable places to start anew—“I’m seeing multiple times a day, every day… people in dire need of housing.

“People pack up their lives and move them into these dwellings, hoping to be able to build a home,” she tells The Coast. “Nobody wants to move every six months. Nobody wants to move every month. That’s really hard on people’s mental health. It’s really hard financially… Nobody wants to go through a state of upheaval every 12 months or less.”