The Titan, the Titanic and the echoes of history – and hubris

HALIFAX – There are now five more souls – for that’s the word they use for maritime disaster – to join the Titanic’s 1,500 in the depths of the Atlantic.

Strange ocean bedfellows these, 12,000 feet down, the Titan and the Titanic, now inseparable in lore, if not permanently on location.

In the coming weeks, the rescue crews that have been frantically trying to locate and rescue the five occupants of the stricken Titan over the past few days will likely remove the submarine’s shattered hull from the ocean floor. It is unlikely they can do the same for the passengers.

As that progresses, the questions begin: the who, the what, the where, the when.

We know – or have partial answers – to some of those questions.

The who: OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush; businessman Shahzada Dawood and his son Suleman Dawood; British billionaire and adventurer Hamish Harding; and Titanic expert Paul-Henri Nargeolet. We know that at least some of them had the means to afford this excursion’s hefty price tag: reportedly on the order of $250,000.

The what: they wanted to see the sinking of the Titanic. OceanGate, which led the expedition, had been ferrying passengers to the wreck for the past two years. There was a layer of scientific observation attached to the field trip, as such observation could be made with limited tools and mostly untrained eyes.

When and where: has yet to be definitively determined, but the location of the debris and the timing of the event make it appear that the Titan was nearing the end of its two-hour descent when it suffered a “catastrophic implosion” – a euphemism for the mighty pressure of the ocean that crushes the hull like an eggshell.

But the biggest question, which will no doubt be the hotly debated topic of the coming weeks, is why?

The question of why it happened is part of it, but also: Why were they there in the first place?

The Titanic, many experts will tell you, was sunk by hubris as well as by an iceberg; the Titan and its occupants, some would say, by ironically disregarding the lessons of history.

In the dark, nearly four kilometers below the surface, the Titanic, the object of their mutual fascination, holds some of the answers.

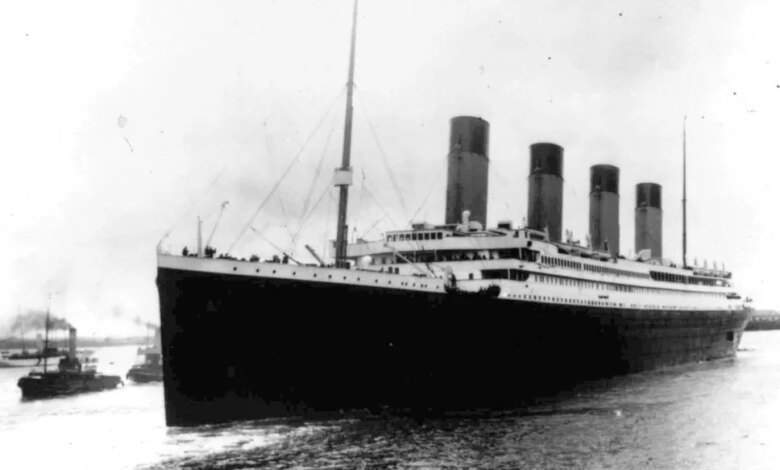

But it wasn’t easy their fascination. From its watery grave, Titanic has gripped the global zeitgeist ever since it collided with an iceberg in April 1912 and sank, killing 1,500 of its 2,200 passengers.

In the intervening 111 years, it has inspired much research in multiple fields, countless books, and yes, movies.

In a world of eroded attention spans, it’s still the only shipwreck that almost anyone, it seems, can identify.

It was “unsinkable,” said owners White Star Line, run by U.S. uber financier JP Morgan. It would be the fastest ship ever, they said. It would bring the owners a lot of money. It was the newest, the biggest, the most fabulous, the most glamorous ship ever made.

But in the rush to get the largest transatlantic liner ever on the water, problems during construction included skimpy rivets, a thin hull, and a lack of lifeboats. Those who raised these issues were ignored when the ship was put to sea.

Halfway through its maiden voyage, moving too fast to avoid an iceberg, it sank and came to rest on the ocean floor nearly four kilometers down.

It became the world’s largest – if least visible – monument to the cost of hubris.

Down there now, 500 meters from the bow of the Titanic, lie the shattered remains of the hull of the submarine Titan.

Tracy Oort is a forensic scientist and continuity officer at Laurentian University and a Titanic investigator. In the course of that investigation, she has been closely involved in identifying the victims and working closely with the families and descendants.

“You had these very wealthy people in the upper echelon, in that first class group of people who financed it, who financed it, who ran it, who were what we would now call influencers.

“And they thought, ‘Hey, I’ve got all this money and I know what I’m doing, and I’ve hired the best shipbuilders and designers. This is going to be a success and it’s going to be the best success and it’s going to beat the competition and we’re going to earn a lot of money.”

“We see this over and over, right? Society is still like that. And I think we are fascinated by that.”

The story of the Titanic is the story of the cost of hubris. It is a story as old as literature itself, a story that never ceases to fascinate us.

It’s the story of Icarus, of Oedipus, of Frankenstein, of the Titanic, even that of Obi-Wan Kenobi and Luke Skywalker.

It’s that, more than anything else, that cements the shipwreck into the public consciousness, Titanic experts say.

“Why do we find that so fascinating? Because we look at our own weaknesses,” says Oort. “Because everyone likes to think they always make good choices.”

Some are fascinated by the demise of the Titanic, a strange sort of gloating as they watch it slowly be reclaimed by a cold, unrelenting, unavoidable ocean.

For others, however, the wreck is a grave, and it pains them to see it open to tourism.

In her experiences with Titanic families, Oort has seen what is called intergenerational grief, the burden of trauma passed down to the family’s descendants.

Valerie Gibson is one of those people. Her grandfather was a second-rate steward on the Titanic. His body has never been found. Until recently – when a museum opened in Southampton, England, home to many of the crew members – his name was never mentioned.

Gibson understands the continued fascination with the Titanic, not just aboard the Titan, but in a much broader sense. She understands the glamour, the pageantry, the underlying appeal of looking, from a distance, at the story of pride before a fall.

But part of the continued fascination was also the social era, she says. And in the early days of mass media, it was the first mass casualty to make headlines all over the world.

Why?

“First, they absolutely claimed it was unsinkable,” she says. “But the second thing, of course, was that it transported very rich people.

“In those days, wealth and money, as now… were everything. If you had no money, you had nothing and you were nobody.

“And the system at the time wasn’t just ‘women and children first,’ it was the rich first.”

She wonders if so much has changed in the next century.

‘It’s tragic, isn’t it? Babies and children almost die in front of people in the Mediterranean. And it’s just, ‘There goes another migrant boat. Oh, yawn.’ It’s terrible.”

Last week, a fishing boat overloaded with migrants trying to reach Europe capsized and sank off the coast of Greece. At least 79 people were killed and hundreds missing.

But almost lost in the lingering fascination with the Titanic, in the tourist trips, in the movies and the books is this: the sinking traumatized thousands, and continues to do so for generations to this day.

Gibson’s mother – six when her father died – never recovered. She couldn’t stand the sound of the ship’s name. Gibson remembers that for the rest of her life when she played a certain song she associated with the Titanic, she burst into tears and ran out of the room.

“She has endured the pain of her mother’s grief, you see. It changed her life and attitude. And of course it changed us – she tore everything up and burned everything that had anything to do with the Titanic.

The point, she says, is that — in a world of increasingly expensive, one-man, adventure tourism — it’s all too often forgotten that the Titanic is also a tomb for so many passengers and crew.

That is a perspective, says Oort, one with which she is very familiar. On the other hand, there is still scientific information to be gleaned from the Titanic.

For example, people previously thought that “rusticles” — bacteria that “eat up” the Titanic’s iron — couldn’t exist in the ocean at that depth, she says.

But that kind of research should be conducted by real scientists with the training, experience and funding to do it right, she believes.

“Two Miles Under the Ocean is not a citizen science project. That is a dangerous environment.”

It’s a delicate trade-off between the two — science and memorial — and one we have to be careful not to throw tourism off balance, she says.

Gibson, for her part, remembers seeing pictures of a boot on the wreck in the early days after the ship’s discovery and wondering if it might have belonged to her grandfather.

“I’m very sad. Just sad for the whole thing. But I wish they left it alone.”

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2023/06/24/the-titan-the-titanic-and-the-echoes-of-history-and-hubris/_1titanic_leaves_southampton.jpg)