Netanyahu: ‘No future’ in Gaza unless ‘Hamas destroyed’ amid concern for hostages

In a recent statement, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu made it clear that the only way for Gaza to have a peaceful future is if Hamas is \”destroyed.\” He emphasized this point following his meetings with President Trump and lawmakers in Washington, where discussions focused on preventing Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons and the need to eliminate Hamas from Gaza.

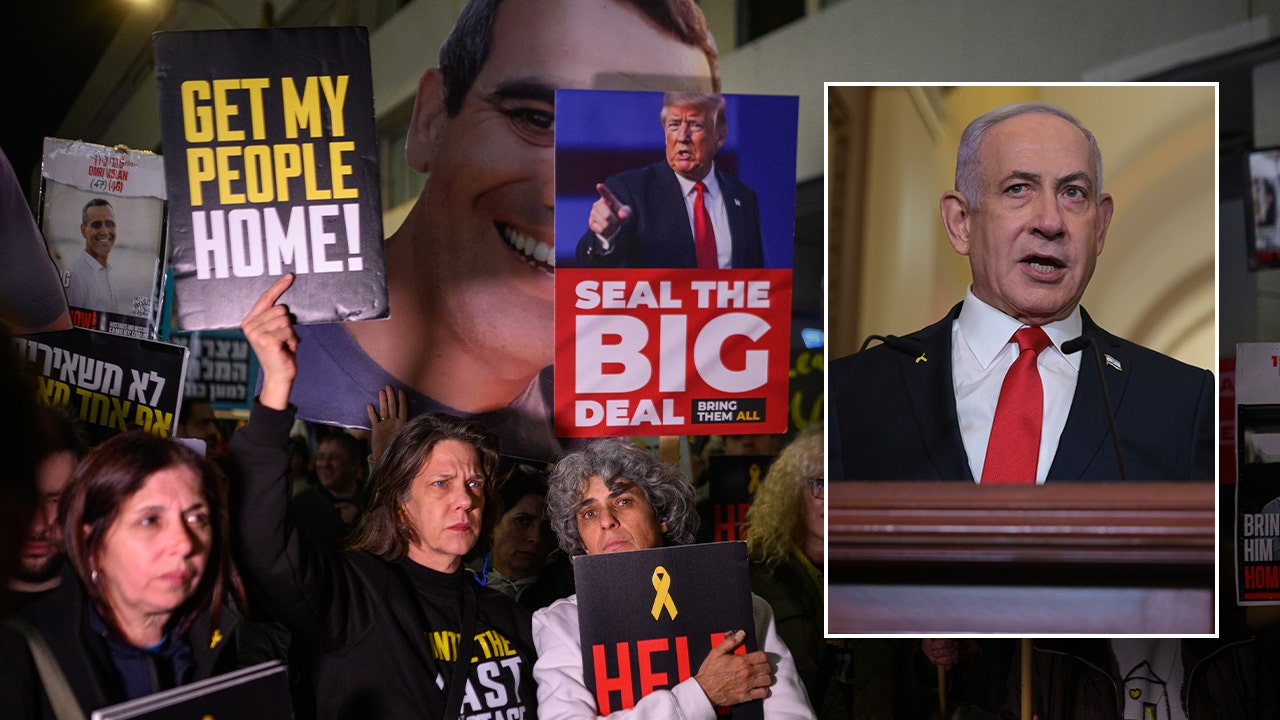

Netanyahu’s strong stance on Hamas has raised concerns among families of hostages still held by the terrorist group. The recent tough rhetoric from Washington, including plans to \”take over\” the Gaza Strip and calls for the mass removal of Palestinians, has sparked fears that it could jeopardize the safe return of the hostages.

One of the concerned voices is Ruby Chen, whose son, Itay Chen, an IDF soldier, was captured by Hamas on Oct. 7. Chen emphasized the importance of prioritizing the release of all hostages before addressing other issues. He urged Netanyahu to focus on the safe return of the hostages taken by Hamas.

Despite the ceasefire agreements, Hamas delayed the release of hostages set to be freed, causing further anxiety among families and mediators involved in the negotiations. Reports indicate that only 13 out of the 33 hostages scheduled for release have been freed so far. Concerns about the fate of the remaining hostages persist, especially after reports of casualties among those held by Hamas.

Netanyahu’s office expressed disappointment over Hamas’ delay in releasing the names of hostages intended to be freed, calling it a \”serious\” violation of the ceasefire agreement. The prime minister will be closely monitoring the hostage release process from Washington, D.C., where he is staying over the weekend.

As negotiations for the second phase of the ceasefire are set to begin, the focus remains on securing the safe return of all hostages held by Hamas. Netanyahu’s commitment to ensuring the safety and well-being of the hostages is paramount, despite the challenges posed by the tough rhetoric from Washington and the ongoing tensions in the region.

The road to peace in Gaza may be fraught with obstacles, but with a unified effort to address the root causes of conflict and prioritize the release of hostages, there is hope for a brighter future for the region. Netanyahu’s unwavering determination to confront Hamas and work towards a peaceful resolution will be crucial in achieving lasting stability in Gaza.